Oral Health and Dentistry

ISSN: 2573-4989

Research Article

Volume 6 Issue 1

The Effect of Background Music on Food Intake among Super Seniors

-

Meikai University, Oral Health Science department

*Corresponding Author: Nobuo Motegi, Meikai University, Oral Health Science department, Akemi Urayasu Chiba 279-8550 Japan.

Abstract

Background: Background music or BGM is likely to impact people’s appetites positively. Although there is massive medical and dental research in music therapy, little is known about the relationship between BGM and food intake in super seniors.

Objectives: This research describes the effect of BGM on the speed and volume of food consumed during meals by the elderly.

Methods: Eleven Japanese self-supported females with an average age of 88.6 who have stayed at the elderly nursing facility were examined. The tests were carried out using two different songs, Classical (Eine Kleine Nachtmusik by Mozart), Jazz music (Sing Sing Sing by Benny Goodman), and no sound while eating their lunch meals. The data was gathered and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics.

Results: Though those who listened to Classical music (23.4 min.) took longer to finish their meal than those who listened to Jazz music (20.8) or no sound (21.8) (P<0.05), there was no change relevant to the food volume consumed among those who listened to Classical (465.5 g), Jazz (424.9) or no sound (465.9). As a result, Classical music seems to contribute to masticatory function or more biting and longer chewing time compared to Jazz music and no sound.

Conclusion: This research implied that listening to Classical music had a more relaxing effect than Jazz music in terms of increasing food consumption time during a lunch meal. The next phase is to increase the number of oldest older participants to accumulate more accurate data.

Keywords: Meal; Classical music; appetites; elderly nursing

Abbreviation: BGM: Background music.

Introduction

Medical treatment can improve organs or tissues. However, it cannot cure mental or psychological conditions. Music has a significant role in medical care and medical therapy (1). Music appreciation substantially encourages people’s activity to spark or inspire their emotional state positively (2). Specifically, when music is taken into the brain, the pitch and melody of sound are dealt with by the hearing field in the temporal lobe, while the cerebellum and motor cortex deal with rhythm. As the element of music is a different part of the brain, musical therapy can activate all aspects of the brain (3).

Music therapy has an impact in a wide variety of medical fields, including mental or psychological amelioration relevant to psychosomatic disease (4) palliative care (5) or terminal care of cancer patients (6), improvement of physiological or endocrine function (7) comprising pulse, temperature, blood pressure (8), brain wave(9), and heart rate (10,11) improvement of lifestyle disease (12), improvement of cranial nerve diseases such as Parkinson disease (13) and Alzheimer disease (14).

Music therapy has recently been implemented through multidisciplinary approaches or interprofessional team collaboration in various places such as hospitals, facilities, and nursing homes (15). Specifically, elderly people who suffer from dementia can relax by listening to BGM and reducing stress and agitation (16).

Music appreciation has a significant influence on the meal environment, and it is suggested that background music or BGM can contribute to a variety of positive impacts on people’s appetite (17). Moreover, BGM types can change taste and odor, pleasure and a general sensation of food stimulation (18).

Specifically, listening to classical music increases a person’s preference for healthy foods or meal pleasure more than that listening to jazz, hip-hop, and rock/metal (19). In addition, when developing musical therapy, listening to Mozart’s classical music enhances the regulation of one’s heartbeat and blood pressure to maintain good health conditions (20).

The weaker elderly tend to have nutrition shortages. They are more likely to have several chronic diseases that could be alleviated with sufficient nutritious food (21). The undernourished elderly seem to have worse health, with more extended hospital visits and a raised death rate (22). Consequently, valuable tactics that could prevent malnutrition among the elderly are needed.

According to J Aging Health, Chronological age, measured as a continuous variable (age in years), was used to group sample persons into 1 of 3 categories: younger older adults (aged 65-69); middle older adults (aged 70-79); and the oldest older adults (aged 80 and older) (23). Additionally, Super-Seniors are healthy, long-lived individuals who were recruited at age 85 or older with no history of cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, dementia, or major pulmonary disease (24).

However, few articles relevant to BGM and food intake can be seen in those aged 80 and older. (25). Additionally, there are few reports or cases in which oldest-older adults were examined, though there is an amount of medical and dental research in music therapy in old age.

This research data was evaluated to find an effective way of using music therapy, including classical, jazz, and no sound. It has been found, a controlled sound environment is indispensable, especially for older ages. This research highlights and defines the effect between BGM and the speed and volume of food consumption during meals among the super seniors...

Materials and Methods

As for the patients of the elderly facility named Eutopia Ebisu, they stay in the nursing home or visit there. Several patients have dementia, strokes, heart diseases, eating disorders, and dysphagia. For measures to be improved, group therapy is carried out for patients to ameliorate discomfort and stress through mutual communication and interaction. Additionally, music therapy has been frequently carried out in this venue. Specifically, the patients practice and play musical instruments. In addition, pronunciation training and oral exercise through chorus are implemented for them.

In this facility, the effect of background music on food intake among seniors were scrutinized. Specifically, eleven Japanese self-supported females or super seniors with an average age of 88.6 who have stayed at the facility were selected under identical conditions such as the same dining room, meals, and music. Additionally, oldest older (aged 80 and above) is a very small population in chronological age. As a result, 11 participants were determined to meet the full requirements. Their gender, age, and general and oral condition were initially inspected.

Firstly, general conditions include medical histories such as diseases, nursing care level from 1 to 5 (level 1: Partial support is a necessity in individual life, Level 2: A more partial level of support is necessary, level 3: Almost all parts of support are necessary to be supported, level 4:all of support, level 5: communication difficulties and complete support necessity), independence in dental chair usage, communication, and staple food, complete diet and food preference. Those over 90 are represented in gray color (Table 1).

| PN | AG | P.H | N.C | D.A | C.M | SF | SD | FP |

| No.1 | 91 | ID | 2 | Y | Y | R | C | No |

| No.2 | 96 | ID,BC | 1 | Y | Y | R | C | No |

| No.3 | 92 | EC | 2 | R | C | No | ||

| No.4 | 81 | HT | 4 | Y | R | C | No | |

| No.5 | 85 | ID, D.A.Z. | 1 | Y | Y | R | C | No |

| No.6 | 85 | ID | 1 | Y | Y | R | C | No |

| No.7 | 89 | HT | 2 | Y | R | C | No | |

| No.8 | 87 | BF,ID | 3 | R | C | No | ||

| No.9 | 81 | HT | 1 | Y | R | C | No | |

| No.10 | 95 | P,G,ID | 2 | R | C | Fish | ||

| No.11 | 87 | HT,ID | 1 | Y | Y | R | C | No |

A.G. : Age, Average88.1; P.N. : Patient Name; P.H. : Past History; I.D. : Infectious disease;

BC : Breast Cancer; EC : Esophagus Cancer; HT : Hypertention; BF : Breast bone Fracture;

P : Pneumonia, G:Goiter; N.C. : Nursing Care Level; D.A. : Sitting Dental Chiar Alone; C.M. : Communication; D.A.Z: Dementia of Alzheimer type; SF : Staple Food; R : Rice; SD. : Side dish; C : Complete Diet; FD. : Food Preference

Table 1: The Items Relevant to Past history & General condition

Secondly, the oral condition including oral cleaning, saliva properties, tongue debris, halitosis, and oral rehabilitation was examined (Table 2).

| ID | OC | PS | TD | HT | OR | UD | LD | RS |

| No.1 | G | S | No | No | No | FD | FD | |

| No.2 | G | S | FD | FD | ||||

| No.3 | G | S | No | No | No | FD | FD | |

| No.4 | G | S | No | No | No | PD | PD | Yes |

| No.5 | G | S | No | No | No | PD | PD | Yes |

| No.6 | A | S | Yes | |||||

| No.7 | A | S | FD | PD | ||||

| No.8 | G | M | No | No | No | PD | PD | Yes |

| No.9 | A | S | FD | FD | Yes | |||

| No.10 | G | M | FD | FD | ||||

| No.11 | G | S | No | No | No | FD | PD | Yes |

OC: Oral cleaning; A: Average; G: Good; PS: Properties of saliva; S: Serous; M: Mucus; TD: Tongue debris; HT:Halitosis; OR: Oral rehabilitation; UD: Upper Denture; LD:Lower Denture; PD:Partial Denture; FD: Full Denture; RS:Rinse

Table 2: The Items Relevant to Oral Condition

Thirdly, the participants’ impression of Classic and Jazz was questioned, five available answers being, 1. Good, 2. Noisy, 3. Too quiet, 4. No interest, 5. The switch (Table 3).

| Cassic | Jazz | ||

| 1 | Good | 29 | 19 |

| 2 | Nosy | 1 | 8 |

| 3 | Too Quiet | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | No Interest | 1 | 4 |

| 5 | Switch | 3 | 6 |

Table 3: Impression of Music

Furthermore, the tests were carried out using two different songs, Classical (Eine Kleine Nachtmusik by Mozart), Jazz music (Sing Sing Sing by Benny Goodman), and no sound during the lunch meal. Super-seniors have no or uncommon experience to listen to hip-hop, and rock/metal in older ages. On the other hand, they are popular to classic and jazz and also particularly, Mozart and Benny Goodman are very popular for Japanese seniors (26).

To gather results, pre and post-food consumption-related food time and volume were measured. These measurements were carried out three times each to both songs, and no sound. The beginning and end of the meal times were measured. The beginning of the meal time could be calculated easily because all participants started to eat their meals simultaneously. Therefore, all start times were the same. However, as the end of each meal time differed between participants, after having had the meal, the participants recorded the time by themselves when having finished eating the meal. The researchers approached their dining table to ensure the participants recorded the time. Photos were taken of the meals twice, at the beginning and the end of eating.

In addition, food volume was measured with Precision Balances EK-i/EW Series (Capacity:120g to 12000g/ Readability: 0.01 g to 1g, Japanese A&D company). Food measurement was shown by ‘g’. The weight relevant to the beginning and end of the meal measured the food, plates, trays, and utensils, including chopsticks and spoons. The food volume consumed by each participant was measured by the difference in weight of their lunch meals before and after consumption. The weight measurements also included their plate, tray, and utensils. These weight measurements were measured using the Precision Balance scale.

What is more, DALI Speaker MENUET MR [Rosso Pair] and Maranz CD Player CD5005 were used to playing BGM. Because when participants are listening to the music, more compact and high-definition devices are needed to be selected to avoid a sense of intimidation and create a comfortable mood when having the meal. Moreover, these devices are located in only one corner of the room, so, not to be recognized easily. Furthermore, the researcher ensured that all participants could listen to background music, including the closest and the furthest from the location. Finally, the data was gathered and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics.

Results

Regarding general condition, those over 90 who are highlighted in a gray color in Table 1, were on average healthier than those under 90, who are shown in white. This can be understood from the over 90's average lower nursing care level than those under 90 (Table 1). In detail, the elderly over 90 were 4 of the 11 subjects, 1/11 had dementia of Alzheimer’s type, and 3/5 suffered from infectious diseases. Regarding staple food, side dish, and food preference, all participants had rice as a staple food and vegetables such as potatoes, carrots, and onions. 10/11 were no food preferences (Table 1). 8/11 people of the elderly implemented oral cleaning, 6/11 rinsed their mouth; saliva was shown that 9/11were serous; others were mucus, tongue debris, halitosis, and oral rehabilitation almost half of the elderly, their denture conditions were 5 people who wore upper and lower full dentures, 3 people who wore both jaws’ partial dentures, 2 people who wore a lower partial denture and an upper full denture, and only one person had upper and lower all-natural teeth. Their masticatory function level was all similar with no obvious problems. Although, this is a variable that could lead to a limitation in our study and leaves room for further research (Table 2).

Additionally, each participant was asked to scale the classical and jazz music after finishing the meal (3 times in each Classic, Jazz, and no sound) as follows: 1. Good, 2. Noisy, 3. Too quiet, 4. No interest, 5. Switch.

Regarding the results of the impression of BGM between Classic and Jazz, Classic is better than Jazz (29:19 answers). At the same time, Jazz is nosier than Classic (8:1 answers). Furthermore, another music is better than Classic or Jazz (3:6 answers) including no answer participants. (Table 3).

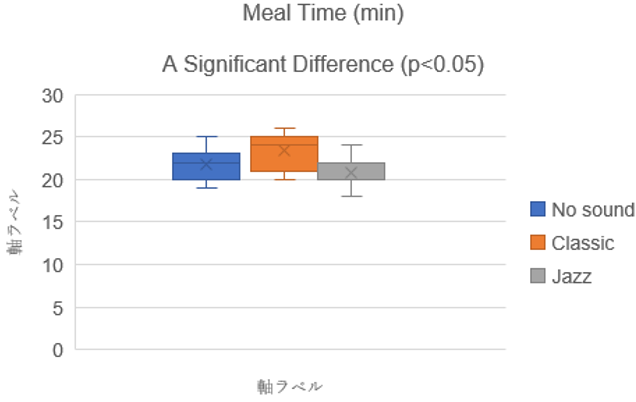

Figure 1: BGM on food intake within super seniors

Those who listened to Classical music took longer to finish their meal than those who listened to Jazz music or no sound.

As a result, Classical music listeners spent longer mealtime compared to Jazz or no-sound listeners ( p<0.05),

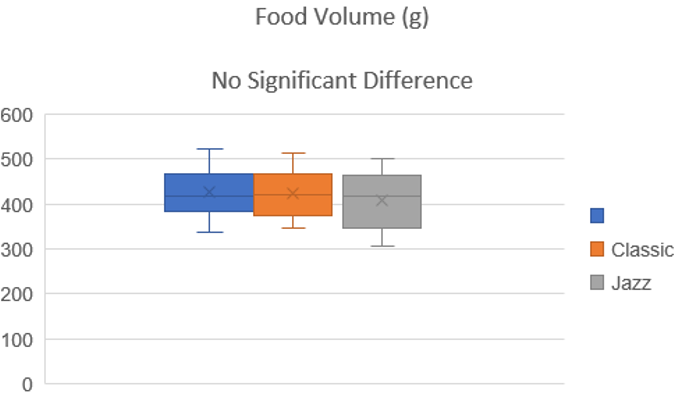

Figure 2: BGM on food intake within super seniors

There was no change relevant to the food volume consumed among those who listened to Classical, Jazz or no sound.

Though those who listened to Classical music took 23.4 minutes on average to finish their meal, which is longer than those who listened to Jazz music who took on average 20.8 minutes or those who listened to no sound who took on average 21.8 minutes (Fig. 1), there was no change relevant to the food volume consumed among those who listened to Classical (465.5 g), Jazz (424.9) or no sound (465.9) (Fig. 2).

As a result, Classical music listeners spent longer mealtime compared to Jazz or no-sound listeners (p<0.05).

Discussions

The speed or tempo of the music is renowned for having a significant impact on promoting food and fluid consumption (27). Music speed can influence the occlusal force, with the effect between the number of bites and music speed (28). Music enhances the food volume and the meal duration (29). Types of music, such as Classical and Jazz music, bring about longer meal duration compared to no sound or pop music (30). As a result, they could spend more time at the table than usual and intake more meals (31).

This research implies that tranquil BGM like Classical music during meals can lead to spending more time at the dining tables and consuming a complete diet or nutritious food. Notably, several recommended sorts of music are soft classical music and music highlighting piano, acoustic guitar, or other stringed instruments. For dementia patients, doctors should advise using the theme without advertisements or commercials and adjusting the appropriate volume or clear sound.

Moreover, Classical BGM impacted cognitive manner and attitude and promoted the contentment of listening to Classical music (32). In addition, Mozart’s music had a robust influence on medical conditions, such as lower the participants’ blood pressure and heart beats (33). Furthermore, Mozart's sonata K 448 can significantly impact brain functional action during the performance of rotation space and mathematical works (34).

When implementing the examination relating to the food volume and speed in detail, the condition of the difference in TMJ structure and physiological function might generally be needed (35,36).However; this research might not be needed for the TMJ diagnosis because these nursing home patients have virtually good oral and health conditions due to wearing compatible dentures and secreting serous saliva (Table2). In other words, they function correctly in terms of biting and chewing or mastication and are healthier than equivalent chronological-aged people. Consequently, this research would not have been given a significant impact on the masticatory condition. In this masticatory condition, the subjects in this group eat not chopped but regular food. A significantly different situation might be considered between food volume and speed if they eat chopped food.

This research was less likely to influence various kinds of food because nearly all participants had no food preference and could finish all of it (Table 1).

What is more, dry mouth might have had an impact on mastication. Participants also took medications, including anti-hypertension, antithrombotic, and ant-platelet drugs. These drugs are more likely to have a relationship with dry mouth (37) because of less salivation (38).

However, most participants did not suffer from dry mouth or xerostomia as they could not find these conditions and symptoms. Moreover, participants didn’t utilize mucosal lubricants, saliva substitutes, or stimulants (39). It was suggested that they conducted oral cleaning every day, and their saliva conditions were serous fluid (Table 2). Consequently, this research is less likely to connect with mouth conditions and mastication.

As for the impression of BGM between Classic and Jazz, Classic is better than Jazz (33:22 answers). At the same time, Jazz is nosier than Classic (8:1 answers). Furthermore, another music is better than Classic or Jazz (3 or 6 answers). (Table 3). It is more likely to prefer calm and slow music than loud and fast, relating to melody and tempo. Listening to Classical music increased saliva volume (40,41). Mastication greatly impacted the secretion volume of saliva, and the volume of masticatory saliva was higher than that of unmasticatory saliva.

As a result, listening to Classical music promotes saliva volume and mastication times compared to those of Jazz and no sound. In terms of this research, the music selected was Eine Kleine Nachtmusik by Mozart, another was Sing Sing Sing by Benny Goodman. However, a wide variety of classical and jazz music can be seen. Accordingly, various pieces of music would be needed to choose when conducting research like this.

Moreover, a wide variety of elements have a significant influence on music impression (42) and inclination, including individuality, background, and history (43). Furthermore, this research was focused on selecting participants with comparatively high healthy level conditions despite being of extreme age or super-age. It might usually be substantially challenging to select those who are healthy as well as elderly.

It was extremely difficult to select these data and implement this research because firstly the oldest old people were small numbers. Additionally, the participants had to arrange an identical environment including the same meals, venue, and conditions.

This research could grasp the tendency that listening to Classical music compared to facilitate a longer meal time in oldest-older adults. As the super seniors or oldest old people have been increasing rapidly over the globe in recent times, gathering and analyzing this data and being analyzed using Data Buffet (44) would have more significant to the current state of the world’s populace age.

Therefore, collecting far more similar cases from various facilities or nursing homes is most likely needed.

Conclusion

This research implied that listening to Classical music (Eine Kleine Nachtmusik) as BGM had a more relaxing effect than that of Jazz music (Sing Sing Sing) in terms of food time meal. When older adults listen to relaxing background music, they can increase the time taken to consume food during a lunch meal more than usual.

However, this research can be further clarified with a larger number of participants of people aged over 80 or 90 over the coming years.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to your cooperation, Motoyuki Hirai, head of the facility of Ebisu-no-Sato and we are grateful to Atsushi Takayanagi, Tokyo Dental College Visiting Associate Professor, because this study was partially supported.

References

- Gabrielsson A, Lindström E. “The influence of musical structure on emotional expression”. Music and Emotion: Theory and Research (2001):223-248.

- Gibson EL. “Emotional influences on food choice: sensory, physiological and psychological pathways”. Physiology Behavior 89.1 (2006): 53-61.

- Trimble M and Sdorffer D. “Music and the brain: the neuroscience of music and musical appreciation”. BJPsych International 14.2 (2017): 28-31.

- Leubner D and Hinterberger T. “Reviewing the Effectiveness of Music Interventions in Treating Depression”. Frontiers in Psychology 8 (2017): 1109.

- Hilliard RE. “Music Therapy in Hospice and Palliative Care: a Review of the Empirical Data”. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2.2 (2005): 173-178.

- Bradt Joke and Dileo C. “Music therapy for end-of-life care”. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 20.1 (2010): 3.

- Akimoto K., et al. “Effect of 528 Hz Music on the Endocrine System and Autonomic Nervous System”. Health 10 (2018 ): 1159-1170.

- Zanini C., et al. “Music therapy effects on the quality of life and the blood pressure of hypertensive patients”. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia 93.5 (2009): 534-540.

- Rahman J., et al. “Brain Melody Interaction: Understanding Effects of Music on Cerebral Hemodynamic Responses”. 6.5 (2022): 35.

- Conference: 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN) At: Glasgow, Scotland

- Zhou Peng., et al. “Music therapy on heart rate variability”. Medicine 2010 3rd International Conference on Biomedical engineering and informatics.

- Akia K., et al. “Effects of Music Therapy on Heart Rate Variabilityin Elderly Patients with Cerebral VascularDisease and Dementia”. Journal of Arrhythmia 22.3 (2006): 161-166.

- Bando H. “Music therapy and internal medicine”. Asian Medical Journal and Alternative Medicine 44.1 (2001): 30-35.

- Garcia CN., et al. “Music Therapy in Parkinson's Disease”. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 19.12 (2018): 1054-1062.

- Leggieri, M., et al. “Music Intervention Approaches for Alzheimer's Disease: A Review of the Literature”. Frontiers in Neuroscience 13 (2019): 132

- Iverson KS. “Relationships between Hospitals' Music Therapy Services and Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (Hcahps) Scores”. Theses and Dissertations (2019):1168.

- Thomas, D W and Smith M. “The Effect of Music on Caloric Consumption Among Nursing Home Residents with Dementia of the Alzheimer's Type”. Activities, Adaption Aging 33.1 (2009): 1-16.

- Woods AT., et al. “Effect of background noise on food perception”. Food Quality and Preference 22.1 (2011): 42-47.

- Fiegel A., et al. “Background music genre can modulate flavor pleasantness and overall impression of food stimuli”. Appetite 76 (2014): 144-152.

- Cui T., et al. “The Relationship between Music and Food Intake: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis”. Nutrients 13.8 (2021): 2571.

- Jaya N and Kadhim S. “Classic Mozart And Murrotal Alquran Therapy Music For Increasing Body Weight In LBW Infants”. Journal of Applied Nursing and Health 4.2 (2022): 272-282.

- Cristina NM and Lucia DA. “Nutrition and Healthy Aging: Prevention and Treatment of Gastrointestinal Diseases”. Nutrients 13.12 (2021): 4337.

- Robinson SM. “Improving nutrition to support healthy ageing: what are the opportunities for intervention?” Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 77.3 (2017): 257-264.

- Choi NG., DiNitto DM., Kim J. “Discrepancy between chronological age and felt age: age group difference in objective and subjective health as correlates”. Journal of Aging and Health 26.3 (2014): 458-473.

- Tindale LC., et al. “10-year follow-up of the Super-Seniors Study: compression of morbidity and genetic factors”. BMC Geriatrics 19.1 (2019): 58.

- Haukkala A. “Emotional eating, depressive symptoms and self-reported food consumption. A population-based study”. Appetite 54.3 (2010): 473-479.

- Kelly WW. “FANNING THE FLAMES, Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan”. 1(2004): 212.

- Mcelrea H and Standing LG. “Fast music causes fast drinking”. Perceptual and Motor Skills 75.2 (1992): 362.

- Thomas CR., et al. “The effect of music on eating behavior”. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society 23 (1985): 221-222.

- Stroebele, N and de Castro JM. “Listening to music while eating is related to increases in people's food intake and meal duration”. Appetite 47.3 (2006): 285-289.

- Wilson S. “The effect of music on parceved atmosphere and purchase intetensions in a restaurant”. Psychology of music 31.1 (2003): 93-112.

- Whear, R., et al. “Effectiveness of mealtime interventions on behavior symptoms of people with dementia living in care homes: a systematic review”. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 15.3 (2014): 185-193.

- Jensen KL. “The effects of selected classical music on self-disclosure”. Journal of Music Therapy 38.1 (2001): 2-27.

- Trappe H-J and Voit G. “The Cardiovascular Effect of Musical Genres”. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 113.20 (2016): 347-352.

- Jausovec N and Habe K. “The influence of Mozart's sonata K. 448 on brain activity during the performance of spatial rotation and numerical tasks”. Brain Topography 17.4 (2005): 207-218.

- Ratnasarik A., et al. “Manifestation of preferred chewing side for hard food on TMJ disc displacement side”. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 38.1 (2011): 12-17

- Irving J., et al. “Does temporomandibular disorder pain dysfunction syndrome affect dietary intake?” Dental Update 26.9 (1999): 405-407.

- Turner MD and Ship JA. “Dry mouth and its effects on the oral health of elderly people”. Journal of the American Dental Association 138.9 (2007): 15S-20S.

- Diep MT., et al. “Xerostomia and hyposalivation among a 65-yr-old population living in Oslo, Norway”. European Journal of Oral Sciences 129.1 (2021): e12757.

- Ferguson MM and Barker MJ. “Saliva substitutes in the management of salivary gland dysfunction”. Advanced drug Delivery Reviews 13.1-2 (1994): 151-159.

- Jin L., et al. “Music stimuli lead to increased levels of nitrite in unstimulated mixed saliva”. Science Ching life Sciences 61.9 (2018): 1099-1106.

- Okuma N., et al. “Effect of masticatory stimulation on the quantity and quality of saliva and the salivary metabolomic profile”. PLoS One 12.8 (2017): e0183109.

- Ballmann C G. “The Influence of Music Preference on Exercise Responses and Performance: A Review”. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 6.2 (2021): 33.

- Christenson PG and Peterson JB. “Genre and gender in the structure of music preferences”. Communication Research 15.3 (1988): 282-301.

- Coccia, C,. et al. “How much and what: Using a buffet to determine self-regulation of food intake among young school-age children”. Physiology Behavior 249 (2022): 113745.

Citation:

Nobuo Motegi., et al. “The Effect of Background Music on Food Intake among Super Seniors”. Oral Health and Dentistry 6.1 (2023): 9-17.

Copyright: © 2023 Dr. Nobuo Motegi., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Scientia Ricerca is licensed and content of this site is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Scientia Ricerca is licensed and content of this site is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.