Review Article

Volume 1 Issue 6 - 2017

Depressed Nasal Bridge in Pediatric Orthopaedic Practice: A Review

Department of Pediatric Orthopaedics, “G Gennimatas” Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece

*Corresponding Author: N K Sferopoulos, Department of Pediatric Orthopaedics, “G Gennimatas” Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece.

Received: October 23, 2017; Published: November 17, 2017

Abstract

Depressions of the nasal bridge may be localized on the bone, cartilage or both. The latter are the most severe cases constituting the saddle-nose deformity, which may lead to various serious functional consequences. A severely depressed nasal dorsum is usually secondary to trauma or infection. In children it may also be caused by a multitude of genetic or environmental factors. A wide variety of congenital disorders or syndromes, birth defects, such as the fetal alcohol syndrome, and infectious diseases, such as congenital syphilis may be included in the pathogenetic factors. The most commonly encounterd congenital syndromes with a depressed nasal bridge in the pediatric orthopaedic practice are cleidocranial dysplasia, children with neurodevelopmental delay, achondroplasia, Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome, Cornelia de Lange syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta and Klippel-Feil syndrome.

The evaluation and management of patients with a depressed nasal bridge requires a ultidisciplinary team. The pediatric orthopaedic surgeon is usually not involved in the primary treatment of these children. However, he may be helpful towards making an early referral, indicating an undiagnosed clinical sign, to establish a syndromic diagnosis and may also be involved in the treatment of coexisting bone disorders.

Review

The depth of the nasal bridge is evaluated from the profile view. The severity of nasal bridge depression as well as the associated clinical findings may vary considerably. In the mild forms the defect causes mainly aesthetic problems, while in the most advanced cases severe airway obstruction and inability to feed may occur. The characteristics of a child are less developed at birth, and with development the nose bridge is likely to acquire a more normal appearance. Saddle depression of the nasal bridge is one of the most common nasal deformities showing varying degrees of severity. It describes nasal profile resembling a riding saddle. It may be relative or true. Relative is when there is a hump formation or excessive projection of the nasal tip or both. In true saddle deformity, there is actual loss of tissues along the dorsal nasal line. Saddle-nose deformity may occur as a result of trauma to the nose (craniofacial trauma, injuries-the boxer’s nose) or as a complication of nasal surgery. It may also be caused by specific infections, such as syphilis, tuberculosis, leprosy, leishmaniasis and other non-specific suppurative infections. In some cases, saddle nose develops from chronic nasal inflammation caused by disorders such as relapsing polychondritis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's granulomatosis). Habitual use of cocaine or inhaling other drugs may cause saddle-nose deformity. Since these deformities may also arise without an evident precipitating cause, they can pose a diagnostic dilemma. The progressing saddle-nose deformity may also be due to sarcoidosis and tumor invasion.

The congenital low nasal bridge or the saddle-nose deformity is a rare occurrence in the pediatric orthopaedic practice. The definition indicates that the deformity is present at birth. The causes may include a birth defect, such as the fetal alcohol syndrome, an infectious disease, such as congenital syphilis, and inherited disorders, such as the ectodermal dysplasias, congenital anomalies due to nose underdevelopment and congenital syndromes, such as dysostosis cleidocranial, Williams syndrome, Down syndrome, achondroplasia, Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome, Cornelia de Lange syndrome, osteogenesis imperfect and Klippel-Feil syndrome. Studies to detect genetic abnormalities or other health problems may include x-rays to estimate the structure of the child’s nose, chromosome tests to detect genetic abnormalities and blood tests to check the level of enzymes and inflammatory markers [1-17].

Birth defects

Fetal alcohol syndrome indicates a wide variety of birth defects associated with the use of alcohol during the first trimester of pregnancy. It may be complicated by nervous system or behavioral problems, facial abnormalities, such as a depressed nasal bridge, growth deficiencies and learning disabilities Alcohol is the most frequent and most important teratogenic noxa for the embryo and fetus [18-21].

Fetal alcohol syndrome indicates a wide variety of birth defects associated with the use of alcohol during the first trimester of pregnancy. It may be complicated by nervous system or behavioral problems, facial abnormalities, such as a depressed nasal bridge, growth deficiencies and learning disabilities Alcohol is the most frequent and most important teratogenic noxa for the embryo and fetus [18-21].

Infectious diseases

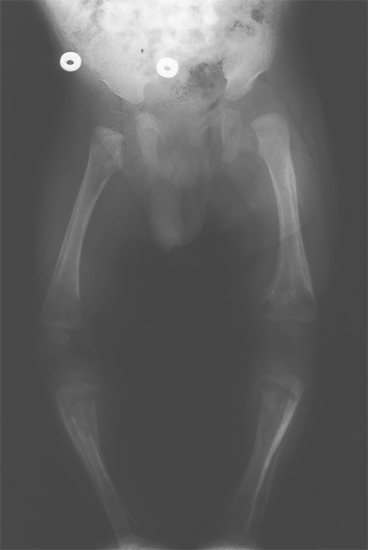

Congenital syphilis is a severe and potentially life-threatening infection in infants caused by Treponema pallidum transmitted by infected mother to her baby almost exclusively via the placental barrier after the fourth month of pregnancy. Perinatal infections are less frequent, and postnatal infections are only exceptionally encountered. The symptoms of congenital syphilis may be divided into prenatal (syphilis materno-fetalis), neonatal, and rarely seen postnatal. Babies born with congenital syphilis frequently have no bridge to nose and severe congenital pneumonia. Associated health problems may include blindness, deafness, neurological problems and skeletal manifestations, including periostitis, osteitis, metaphyseal changes (Figure 1), pseudoparalysis, pathological fractures, joint involvement and dactylitis. Penicillin is the only antibiotic of proven value for the treatment of congenital syphilis [22-26].

Congenital syphilis is a severe and potentially life-threatening infection in infants caused by Treponema pallidum transmitted by infected mother to her baby almost exclusively via the placental barrier after the fourth month of pregnancy. Perinatal infections are less frequent, and postnatal infections are only exceptionally encountered. The symptoms of congenital syphilis may be divided into prenatal (syphilis materno-fetalis), neonatal, and rarely seen postnatal. Babies born with congenital syphilis frequently have no bridge to nose and severe congenital pneumonia. Associated health problems may include blindness, deafness, neurological problems and skeletal manifestations, including periostitis, osteitis, metaphyseal changes (Figure 1), pseudoparalysis, pathological fractures, joint involvement and dactylitis. Penicillin is the only antibiotic of proven value for the treatment of congenital syphilis [22-26].

Figure 1: Radiograph of a 5-month-old girl with congenital syphilis showing bilateral femoral periosteal reaction and multifocal metaphyseal symmetrical erosions in the lower limbs.

Inherited disorders

Because of the saddle-nose deformity and bilateral cataracts all patients suspected of having congenital syphilis should be investigated for ocular or auditory defects, which would confirm the diagnosis of ectodermal dysplasia. Ectodermal dysplasias are a large and complex group of inherited disorders characterized by deficient ectodermal and mesodermal development. Nasal obstruction due to the presence of nasal crusting, hearing loss and throat hoarseness are the most represented symptoms [27-30].

Because of the saddle-nose deformity and bilateral cataracts all patients suspected of having congenital syphilis should be investigated for ocular or auditory defects, which would confirm the diagnosis of ectodermal dysplasia. Ectodermal dysplasias are a large and complex group of inherited disorders characterized by deficient ectodermal and mesodermal development. Nasal obstruction due to the presence of nasal crusting, hearing loss and throat hoarseness are the most represented symptoms [27-30].

Congenital anomalies of the nose include a broad spectrum of defects, being a result of abnormalities in the developmental process. These conditions range from partial deformities of the nose, such as isolated absence of the nasal bones, absence of the columella, absence of the septal cartilage or alae cartilage, through hemi aplasia of the nose to complete absence of the nose (arhinia) [17].

Congenital syndromes

The nasal bridge may be depressed, or lie deeper in the face than normal, in various craniosynostosis syndromes and skeletal dysplasias. The most common congenital skeletal dysplasias that may be associated with a low nasal bridge in the pediatric orthopaedic practice are:

The nasal bridge may be depressed, or lie deeper in the face than normal, in various craniosynostosis syndromes and skeletal dysplasias. The most common congenital skeletal dysplasias that may be associated with a low nasal bridge in the pediatric orthopaedic practice are:

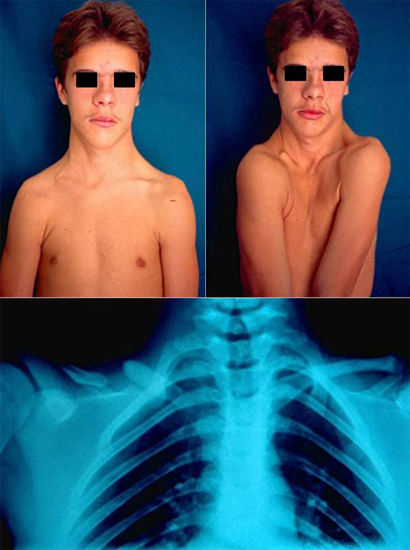

1. Cleidocranial dysplasia is a well defined skeletal and dental disorder with characteristic clinical findings and autosomal dominant inheritance. Major indicators of the disease include hypoplasia or aplasia of clavicular bones. Bilaterality is the rule but not always the case (Figure 2). The missing segment may be represented by fibrous pseudarthrosis or by a fibrous tether or cord. Craniofacial growth is affected in many ways and may include a depressed nasal bridge. The thoracic cage is small and bell shaped with short, oblique ribs. The pelvis is invariably involved and shows characteristic changes. A relatively constant abnormality is the presence of both proximal and distal epiphyses in the second metacarpals and metatarsals leading to excessive growth and length. All other bones of the hands and feet, especially the distal phalanges and the middle phalanges of the second and fifth fingers are unusually short. Final height is significantly reduced. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle is probably among the most common conditions to be differentiated. It was initially described in association with cleidocranial dysplasia. In the great majority of cases involvement is unilateral with a marked predominance of the right side. The cases are sporadic and there is no other bone involvement [31-35].

Figure 2: Clinical appearance and radiograph of a 13-year-old boy with cleidocranial dysplasia and unilateral involvement of the right clavicle. The most prominent facial signs are the absence of the nasal bone, bossing of the frontal bones, prominent chin and maxillary hypoplasia, which typify the characteristic appearance of those afflicted with this syndrome.

2. Neurodevelopmental delay and dysmorphic facial features require a thorough evaluation and extensive diagnostic testing in children (Figure 3). A) Williams syndrome is a developmental disorder caused by a hemizygous contiguous gene deletion on chromosome 7q11.23. It is characterized by distinct facial features, congenital heart disease, mental retardation and a gregarious personality. It may also be complicated by bone deformities like a depressed nose [36-39]. B) Down syndrome also known as trisomy 21, is the most common chromosomal abnormality among live born infants reaching up to 1 in 700 births. It is typically associated with physical growth delays, characteristic facial features and mild to moderate intellectual disability. It is characterized by a variety of dysmorphic features and medical conditions. The former include a small chin, slanted eyes, poor muscle tone, a flat nasal bridge, a single crease of the palm, and a protruding tongue due to a small mouth and relatively large tongue. The latter include poor immune function, congenital heart defect, atlantoaxial instability, epilepsy, leukemia, thyroid diseases, and mental disorders. Children with Down syndrome are at increased risk of ear-nose-throat disorders such as refractory otitis, eustachian tube dysfunction, laryngomalacia, tracheal stenosis, obstructive sleep apnea, hearing loss, as well as voice and articulatory impairments [40-44].

Figure 3: Clinical appearance and radiograph of an 18-month-old girl with neurodevelopmental delay, postaxial polydactyly of hands and feet and dysmorphic facial features with a depressed nasal bridge.

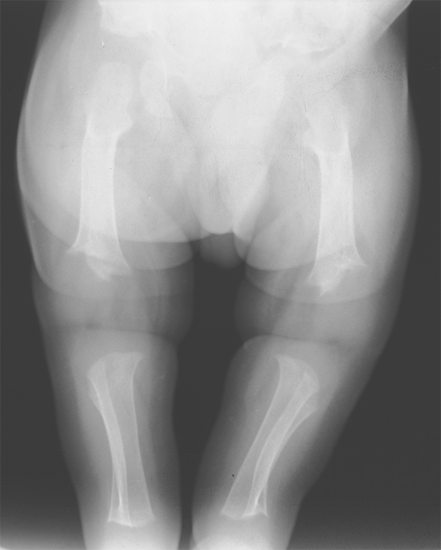

3. Achondroplasia is a human bone genetic disorder of the growth plate and is the most common form of inherited disproportionate short stature. It is inherited as an autosomal dominant disease with essentially complete penetrance. Of these most have the same point mutations in the gene for fibroblast growth factor receptor 3, which is a negative regulator of bone growth. The clinical and radiological features of achondroplasia may easily be identified; they include disproportionate short stature with rhizomelic shortening, lumbar hyperlordosis, and a trident hand configuration. Achondroplasia is also of dental interest because of its characteristic craniofacial features which include relative macrocephaly with frontal bossing (prominent or bulging forehead with a depressed nasal bridge), midface hypoplasia and maxillary hypoplasia (Figure 4a and b). The majority of achondroplasts have a normal intelligence, but many social and medical complications may compromise a full and productive life. Some of them have serious health consequences related to hydrocephalus, craniocervical junction compression, or upper-airway obstruction [45-49].

Figure 4a: Radiograph of a 6-month-old boy with achondroplasia (a). The pronounced shortening of the proximal limb segments, with the humeri most severely affected, and the characteristic craniofacial features, including a depressed nasal bridge, are evident in this 11-year-old girl (b).

Figure 4b: Radiograph of a 6-month-old boy with achondroplasia (a). The pronounced shortening of the proximal limb segments, with the humeri most severely affected, and the characteristic craniofacial features, including a depressed nasal bridge, are evident in this 11-year-old girl (b).

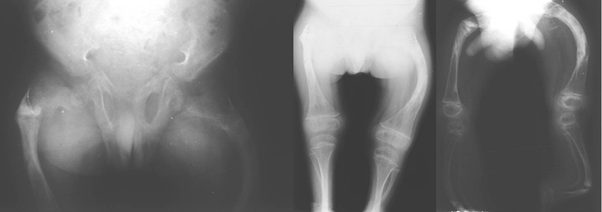

4. The Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome is characterized by dysmorphic face with depressed nasal bridge, skin manifestations, heart defects, cataract, hypotonia, short stature, kyphoscoliosis, coxa vara, upper cervical instability and stippled calcifications within the epiphyses. Chondrodysplasia punctata (CDP) is a rare, heterogeneous congenital skeletal dysplasia, characterized by punctate or dot-like calcium deposits in cartilage observed on neonatal radiograms (Figure 5). A number of inborn metabolic diseases are associated with CDP, including peroxisomal and cholesterol biosynthesis dysfunction and other inborn errors of metabolism such as: mucolipidosis type II, mucopolysacharidosis type III, GM1 gangliosidosis. CDP can be seen in several disorders and syndromes such as Turner, Zellweger, trisomy 21, trisomy 18, FAS and following ingestion of warfarin or phenytoin during pregnancy. The inheritance transmission may be autosomal dominant type, autosomal recessive type, X-linked dominant type, X-linked recessive type with deletion of terminal short arm or duplication of short arm of chromosome 16 [50-67].

Figure 5: Clinical appearance and radiograph of a 4-month-old girl with depressed nasal bridge and stippled calcification within the epiphyses of the lower limbs typical of chondrodysplasia punctata.

5. Cornelia de Lange syndrome (also called Bushy syndrome or Amsterdam dwarfism), is a genetic disorder that can lead to several alterations. This disease affects both physical and neuropsychiatric development. The various abnormalities include facial dysmorphia (arched eyebrows, synophrys, depressed nasal bridge, long philtrum, down-turned angles of the mouth), upper-extremity malformations, hirsutism, cardiac defects, and gastrointestinal alterations. Classical de Lange syndrome presents with a striking face, pronounced growth and mental retardation, and variable limb deficiencies (Figure 6a, b). Over the past five years, a mild variant has been defined, with less significant psychomotor retardation, less marked pre- and postnatal growth deficiency, and an uncommon association with major malformations, although mild limb anomalies may be present [68-76].

Figure 6a: Clinical appearance of a 6-month-old boy with the typical dysmorphic facial features of Cornelia de Lange syndrome including synophrys, long curly eye lashes, low anterior and posterior hair line, underdeveloped orbital arches, arched eyebrows, long philtrum, anteverted nares, down-turned angles of the mouth, thin lips, depressed nasal bridge, and micrognathia. He also had a short neck, hirsutism, relatively small hands and feet, and congenital dyspigmentation on his right foot (a). Clinical appearance of a 4-year-old boy that demonstrated short stature, microcephaly, mental retardation, and bushy eyebrows that meet in the midline, a depressed nasal bridge, and full eyelashes. There was a single palmar crease on both palms, ulnar polydactyly on the left hand and dysplasia of the distal phalanx of the little finger with bone-nail hypertrophy. The findings were typical of Cornelia de Lange syndrome (b).

Figure 6b: Clinical appearance of a 6-month-old boy with the typical dysmorphic facial features of Cornelia de Lange syndrome including synophrys, long curly eye lashes, low anterior and posterior hair line, underdeveloped orbital arches, arched eyebrows, long philtrum, anteverted nares, down-turned angles of the mouth, thin lips, depressed nasal bridge, and micrognathia. He also had a short neck, hirsutism, relatively small hands and feet, and congenital dyspigmentation on his right foot (a). Clinical appearance of a 4-year-old boy that demonstrated short stature, microcephaly, mental retardation, and bushy eyebrows that meet in the midline, a depressed nasal bridge, and full eyelashes. There was a single palmar crease on both palms, ulnar polydactyly on the left hand and dysplasia of the distal phalanx of the little finger with bone-nail hypertrophy. The findings were typical of Cornelia de Lange syndrome (b).

6. Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) or brittle bone disease is a rare hereditary disorder of type 1 collagen synthesis with a triad of clinical features including multiple fractures, blue sclera and conductive hearing loss. It exhibits wide variation in appearance and severity. The most severe forms lead to early death. Clinical features such as fracture frequency, long bone deformities (Figure 7a), muscle strength or extraskeletal problems vary widely. Some features are age dependent. The initial classification by Looser described two types: OI congenita and OI tarda. Sillence and colleagues described 4 types of the disease taking into account the phenotypic features and the mode of inheritance. Scleral hue is an important sign which distinguishes 2 broad groupings of patients, those with and those without blue sclera, with nonlethal OI. Individuals with OI type I (Figure 7b) have distinctly blue sclerae which remain intensely blue throughout life. In OI type III and OI type IV the sclerae may also be blue at birth and during infancy, but the intensity fades with time such that these individuals have sclerae of normal hue by adolescence and adult life. In children with the most severe nonlethal forms of osteogenesis imperfecta severe craniofacial and dental anomalies may be encountered, although there are only very few reported OI patients treated with rhinoplasty [77-81].

Figure 7a: A 5-year-old boy, with kyphoscoliosis, abnormal teeth and short stature, suffering from type III osteogenesis imperfect. Considerable deformity of the femora and tibiae, fractures developing callus formation and pseudarthrosis at sites of healing fractures were evident on radiographs (a). Clinical appearance of a 9-year-old girl, with blue sclera and mildly depressed nasal bridge, suffering from type I-A (normal teeth) osteogenesis imperfecta (b).

Figure 7b: A 5-year-old boy, with kyphoscoliosis, abnormal teeth and short stature, suffering from type III osteogenesis imperfect. Considerable deformity of the femora and tibiae, fractures developing callus formation and pseudarthrosis at sites of healing fractures were evident on radiographs (a). Clinical appearance of a 9-year-old girl, with blue sclera and mildly depressed nasal bridge, suffering from type I-A (normal teeth) osteogenesis imperfecta (b).

7. The Klippel-Feil syndrome may be associated with osseous and visceral anomalies. It usually presents with a clinical triad including a short tilted neck, low posterior hairline, and loss of the cervical motion. It is characterized by the fusion of at least two cervical vertebrae. An unrecognized fetal alcohol syndrome has been questioned in the pathogenesis, although the two syndromes are distinct entities. A variety of craniofacial anomalies, including a depressed nasal bridge (Figure 8), may occur, in association with the syndrome, widening its clinical spectrum [82-92].

Figure 8: Clinical appearance of a 2-month-old boy with Klippel-Feil syndrome that presented with a depressed nasal bridge and a painless congenital torticollis. Subaxial synostosis of the cervical spine was evident on radiographs at the age of 3 years.

Other rare congenital disorders associated with depressed nasal bridge are the Larsen syndrome [93], the Pallister-Killian syndrome [94], the Joubert syndrome [95], the Timothy syndrome [96], the Fraccaro syndrome [97], the Holt-Oram syndrome [98], the Stickler syndrome [99], the Costello syndrome [100], etc.

Depressed nasal bridge is a rare and probably underestimated condition in neonates. It may be due to a wide variety of disorders with completely different phenotype and genotype. The pathogenic pathway in causing the specific anomaly is completely different in each disorder. Pediatric consultation through an early referral is essential for a successful early identification, prompt diagnosis and therapy of infants with a depressed nasal bridge or a saddle-nose deformity due to birth defects, infectious diseases, inherited disorders and congenital syndromes.

Conflict of interest statement: The author certifies that he has no commercial associations (such as consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article. The author received no financial support for this study.

References

- Strachan JG. “Some observations on ‘saddle-nose’ deformity in children”. Canadian Medical Association Journal 17.3 (1927): 324-326.

- Diwan VS. “The depressed nose in leprosy”. British Journal of Plastic Surgery 21.3 (1968): 295-320.

- Beekhuis GJ. “Saddle nose deformity: etiology, prevention, and treatment; augmentation rhinoplasty with polyamide”. The Laryngoscope 84.1 (1974): 2-42.

- Magalon G., et al. “Congenital saddle nose. Clinical aspect and treatment. Apropos of 7 cases”. Ann Chir Plast Esthet 24.2 (1979): 149-152.

- Baser B., et al. “Management of saddle nose deformity in atrophic rhinitis”. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology 104.5 (1990): 404-407.

- Graper C., et al. “The traumatic saddle nose deformity: etiology and treatment”. The Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Trauma 2.1 (1996): 37-49; discussion 50-51.

- Worley GA., et al. “Pyoderma gangrenosum producing saddle nose deformity”. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology 112.9 (1998): 870-871.

- Merkonidis C., et al. “Saddle nose deformity in a patient with Crohn's disease”. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology 119.7 (2005): 573-576.

- Shine NP., et al. “Takayasu's arteritis and saddle nose deformity: a new association”. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology 120.1 (2006): 59-62.

- Daniel RK and Brenner KA. “Saddle nose deformity: A new classification and treatment”. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America 14.4 (2006): 301-312, vi.

- Coudurier M., et al. “Saddle nose deformity”. La Revue du praticien 57.17 (2007): 1863.

- Wu F and Hao SP. “Rosai-Dorfman disease presented as saddle nose”. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 138.1 (2008): 124-125.

- Pribitkin EA and Ezzat WH. “Classification and treatment of the saddle nose deformity”. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America 42.3 (2009): 437-461.

- Pereyra-Rodríguez JJ., et al.” Saddle nose deformity”. Medicina Clínica (Barcelona) 136.1 (2011): 44.

- Durbec M and Disant F. “Saddle nose: classification and therapeutic management”. European Annals of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Diseases 131.2 (2014): 99-106.

- Schreiber BE., et al. “Saddle-nose deformities in the rheumatology clinic”. Ear, Nose, & Throat Journal 93.4-5 (2014): E45-47.

- Fijałkowska M and Antoszewski B. “Nose underdevelopment - etiology, diagnosis and treatment”. Otolaryngologia polska 70.2 (2016): 13-18.

- Abel EL. “Prenatal effects of alcohol”. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 14.1 (1984): 1-10.

- Warren KR and Bast RJ. “Alcohol-related birth defects: an update”. Public Health Reports 103.6 (1988): 638-642.

- Pećina-Hrncević A and Buljan L. “Fetal alcohol syndrome-case report”. Acta stomatologica Croatica 25.4 (1991): 253-258.

- Ripabelli G., et al. “Alcohol consumption, pregnancy and fetal alcohol syndrome: implications in public health and preventive strategies”. Annali Di Igiene 18.5 (2006): 391-406.

- Hollier LM and Cox SM. “Syphilis”. Semin Perinatol 22.4 (1998): 323-331.

- Carey JC. “Congenital syphilis in the 21st century”. Curr Womens Health Rep 3.4 (2003): 299-302.

- Saloojee H., et al. “The prevention and management of congenital syphilis: an overview and recommendations”. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 82.6 (2004): 424-430.

- Kremenová S., et al. “Issues of congenital syphilis in the past twenty years. II. Clinical picture”. Klinicka Mikrobiologie a Infekcni Lekarstvi 12.2 (2006): 51-57.

- Milanez H. “Syphilis in pregnancy and congenital syphilis: Why can we not yet face this problem?” Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia 38.9 (2016): 425-427.

- Onile BA., et al. “Marshall syndrome: a condition resembling congenital syphilis”. The British Journal of Venereal Diseases 57.2 (1981): 100-102.

- Gil-Carcedo LM. “The nose in anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia”. Rhinology 20.4 (1982): 231-235.

- Mehta U., et al. “Head and neck manifestations and quality of life of patients with ectodermal dysplasia”. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 136.5 (2007): 843-847.

- Callea M., et al. “Ear nose throat manifestations in hypoidrotic ectodermal dysplasia”. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 77.11 (2013): 1801-1804.

- Jarvis JL and Keats TE. “Cleidocranial dysostosis. A review of 40 new cases”. The American Journal of Roentgenology Radium Therapy and Nuclear Medicine 121.1 (1974): 5-16.

- Mundlos S. “Cleidocranial dysplasia: clinical and molecular genetics”. Journal of Medical Genetics 36.3 (1999): 177-182.

- Cadilhac C., et al. “Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle: 25 childhood cases”. Revue de chirurgie orthopedique et reparatrice de l'appareil moteur 86.6 (2000): 575-580.

- Golan I., et al. “Early craniofacial signs of cleidocranial dysplasia”. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 14.1 (2004): 49-53.

- Back SJ and Pollock AN. “Cleidocranial dysostosis”. Pediatric Emergency Care 29.7 (2013): 867-869.

- Wu YQ., et al. “Delineation of the common critical region in Williams syndrome and clinical correlation of growth, heart defects, ethnicity, and parental origin”. American Journal of Medical Genetics 78.1 (1998): 82-89.

- van Hagen JM., et al. “Williams syndrome: new insights into genetic etiology, pathogenesis and clinical aspects”. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde 145.9 (2001): 396-400.

- Collette JC., et al. “William's syndrome: gene expression is related to parental origin and regional coordinate control”. Journal of Human Genetics 54.4 (2009): 193-198.

- Schubert C. “The genomic basis of the Williams-Beuren syndrome”. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 66.7 (2009): 1178-1197.

- Ferrario VF., et al. “Soft tissue facial anthropometry in Down syndrome subjects”. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 15.3 (2004): 528-532.

- de Moura CP., et al. “Rapid maxillary expansion and nasal patency in children with Down syndrome”. Rhinology 43.2 (2005): 138-142.

- Ramia M., et al. “Revisiting Down syndrome from the ENT perspective: review of literature and recommendations”. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 271.5 (2014): 863-869.

- Chin CJ., et al. “A general review of the otolaryngologic manifestations of Down syndrome”. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 78.6 (2014): 899-904.

- Paul D MA., et al. “Ear, nose and throat disease profile in children with Down syndrome”. Revista Chilena De Pediatria 86.5 (2015): 318-324.

- Horton WA., et al. “Achondroplasia”. Lancet 370.9582 (2007): 162-172.

- Baujat G., et al. “Achondroplasia”. Best Practice & Research: Clinical Rheumatology 22.1 (2008): 3-18.

- Al-Saleem A and Al-Jobair A. “Achondroplasia: Craniofacial manifestations and considerations in dental management”. The Saudi Dental Journal 22.4 (2010): 195-199.

- Rohilla S., et al. “Orofacial manifestations of achondroplasia”. EXCLI Journal 11 (2012): 538-542.

- Bouali H and Latrech H. “Achondroplasia: Current Options and Future Perspective”. Pediatric Endocrinology Reviews 12.4 (2015): 388-395.

- Frank WW and Denny MG. “Dysplasia epiphysialis punctata; report of a case and review of literature”. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume 36.1 (1954): 118-22.

- Hall JG., et al. “Maternal and fetal sequelae of anticoagulation during pregnancy”. The American Journal of Medicine 68.1 (1980): 122-140.

- Andersen PE Jr and Justesen P. “Chondrodysplasia punctata. Report of two cases”. Skeletal Radiology 16.3 (1987): 223-226.

- Tamburrini O., et al. “Chondrodysplasia punctata after warfarin. Case report with 18-month follow-up”. Pediatric Radiology 17.4 (1987): 323-324.

- Hernández J., et al. “Chondrodysplasia punctata associated with Down's syndrome. Presentation of a case and review of the literature”. Anales Espanoles De Pediatria 28.2 (1988): 145-147.

- Leicher-Düber A., et al. “Stippled epiphyses in fetal alcohol syndrome”. Pediatric Radiology 20.5 (1990): 369-370.

- Wulfsberg EA., et al. “Chondrodysplasia punctata: a boy with X-linked recessive chondrodysplasia punctata due to an inherited X-Y translocation with a current classification of these disorders”. American Journal of Medical Genetics 43.5 (1992): 823-828.

- Seguin JH., et al. “Airway manifestations of chondrodysplasia punctate”. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 27.1 (1993): 85-90.

- Omobono E and Goetsch W. “Chondrodysplasia punctata (the Conradi-Hünermann syndrome). A clinical case report and review of the literature”. Minerva Pediatrica 45.3 (1993): 117-121.

- Poznanski AK. “Punctate epiphyses: a radiological sign not a disease”. Pediatric Radiology 24.6 (1994): 418-424, 436.

- Corbí MR., et al. “Conradi-Hünermann syndrome with unilateral distribution”. Pediatric Dermatology 15.4 (1998): 299-303.

- Morrison SC. “Punctate epiphyses associated with Turner syndrome”. Pediatric Radiology 29.6 (1999): 478-480.

- Traupe H and Has C. “The Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome is caused by mutations in the gene that encodes a 8- 7 sterol isomerase and is biochemically related to the CHILD syndrome”. European Journal of Dermatology 10.6 (2000): 425-428.

- Mason DE., et al. “Spinal deformity in chondrodysplasia punctate”. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 27.18 (2002): 1995-2002.

- Rakheja D., et al. “A severely affected female infant with x-linked dominant chondrodysplasia punctata: a case report and a brief review of the literature”. Pediatric and Developmental Pathology 10.2 (2007): 142-148.

- Shanske AL., et al. “Chondrodysplasia punctata and maternal autoimmune disease: a new case and review of the literature”. Pediatrics 120.2 (2007): e436-441.

- Irving MD., et al. “Chondrodysplasia punctata: a clinical diagnostic and radiological review”. Clinical Dysmorphology 17.4 (2008): 229-241.

- Jurkiewicz E., et al. “Clinical and radiological pictures of two newborn babies with manifestations of chondrodysplasia punctata and review of available literature”. Polish Journal of Radiology 78.2 (2013): 57-64.

- McArthur RG and Edwards JH. “De Lange syndrome: report of 20 cases”. Canadian Medical Association Journal 96.17 (1967): 1185-1198.

- Ireland M and Burn J. “Cornelia de Lange syndrome-photo essay”. Clinical Dysmorphology 2.2 (1993): 151-160.

- Saul RA., et al. “Brachmann-de Lange syndrome: diagnostic difficulties posed by the mild phenotype”. American Journal of Medical Genetics 47.7 (1993): 999-1002.

- Allanson JE., et al. “De Lange syndrome: subjective and objective comparison of the classical and mild phenotypes”. Journal of Medical Genetics 34.8 (1997): 645-650.

- Strachan T. “Cornelia de Lange Syndrome and the link between chromosomal function, DNA repair and developmental gene regulation”. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 15.3 (2005): 258-264.

- Schoumans J., et al. “Comprehensive mutational analysis of a cohort of Swedish Cornelia de Lange syndrome patients”. European Journal of Human Genetics 15.2 (2007): 143-149.

- Guadagni MG., et al. “Cornelia de Lange syndrome: description of the orofacial features and case report”. European Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 9.4 Suppl (2008): 9-13.

- Liu J and Baynam G. “Cornelia de Lange syndrome”. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 685 (2010): 111-123.

- Leanza V., et al. “Case Report: Atypical Cornelia de Lange Syndrome”. Version 2. F1000Res 3 (2014): 33.

- Ende MJ and Horn KL. “Rhinoplasty and osteogenesis imperfecta”. Ear, Nose, & Throat Journal 56.8 (1977): 325-327.

- Bergstrom L. “Osteogenesis imperfecta: otologic and maxillofacial aspects”. Laryngoscope 87.9 Pt 2 Suppl 6 (1977): 1-42.

- Sillence D., et al. “Natural history of blue sclerae in osteogenesis imperfecta”. American Journal of Medical Genetics 45.2 (1993): 183-186.

- O'Connell AC and Marini JC. “Evaluation of oral problems in an osteogenesis imperfecta population”. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology 87.2 (1999): 189-196.

- Bilkay U., et al. “Management of nasal deformity in osteogenesis imperfecta”. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 21.5 (2010): 1465-1467.

- Tredwell SJ., et al. “Cervical spine anomalies in fetal alcohol syndrome”. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 7.4 (1982): 331-334.

- Fragoso R., et al. “Frontonasal dysplasia in the Klippel-Feil syndrome: a new associated malformation”. Clinical Genetics 22.5 (1982): 270-273.

- Pfeiffer RA., et al. “An autosomal dominant facio-audio symphalangism syndrome with Klippel-Feil anomaly: a new variant of multiple synostoses”. Genetic Counseling 1.2 (1990): 133-140.

- Schilgen M and Loeser H. “Klippel-Feil anomaly combined with fetal alcohol syndrome”. European Spine Journal 3.5 (1994): 289-290.

- Erol M., et al. “Report of a girl with Klippel-feil syndrome and Poland anomaly”. Genetic Counseling 15.4 (2004): 469-472.

- Samartzis D., et al. “Sprengel's deformity in Klippel-Feil syndrome”. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 32.18 (2007): E512-516.

- Naikmasur VG., et al. “Type III Klippel-Feil syndrome: case report and review of associated craniofacial anomalies”. Odontology 99.2 (2011): 197-202.

- Samartzis D., et al. “Cervical scoliosis in the Klippel-Feil patient”. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 36.23 (2011): E1501-1508.

- Bindoudi A., et al. “The rare sprengel deformity: our experience with three cases”. Journal of Clinical Imaging Science 4 (2014): 55.

- Samartzis D., et al. “‘Clinical triad’ findings in pediatric Klippel-Feil patients”. Scoliosis and Spinal Disorders 11 (2016): 15.

- Saker E., et al. “The intriguing history of vertebral fusion anomalies: the Klippel-Feil syndrome”. Child's Nervous System 32.9 (2016): 1599-1602.

- Liang CD and Hang CL. "Elongation of the aorta and multiple cardiovascular abnormalities associated with larsen syndrome”. Pediatric Cardiology 22.3 (2001): 245-246.

- Bagattoni S., et al. “Oro-dental features of Pallister-Killian syndrome: Evaluation of 21 European probands”. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part 170.9 (2016): 2357-2364.

- De Mori R., et al. “Hypomorphic Recessive Variants in SUFU Impair the Sonic Hedgehog Pathway and Cause Joubert Syndrome with Cranio-facial and Skeletal Defects”. The American Journal of Human Genetics 101.4 (2017): 552-563.

- Napolitano C., et al. “Timothy Syndrome”. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Mefford HC, Stephens K, Amemiya A, Ledbetter N, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2017.

- Hadipour F., et al “Fraccaro syndrome: report of two Iranian cases: an infant and an adult in a family”. Acta Medica Iranica 51.12 (2013): 907-909.

- Aviña-Fierro JA and Colonnelli-Barba G. “Holt-Oram syndrome associated with facial anomalies. A case report”. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc 48.6 (2010): 657-659.

- Snead MP and Yates JR. “Clinical and Molecular genetics of Stickler syndrome”. Journal of Medical Genetics 36.5 (1999): 353-359.

- Der Kaloustian VM., et al. “Costello syndrome”. American Journal of Medical Genetics 41.1 (1991): 69-73.

Citation:

N K Sferopoulos. “Depressed Nasal Bridge in Pediatric Orthopaedic Practice: A Review”. Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology

1.6 (2017): 225-236.

Copyright: © 2017 N K Sferopoulos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Scientia Ricerca is licensed and content of this site is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Scientia Ricerca is licensed and content of this site is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.