Conceptual Paper

Volume 2 Issue 2 - 2018

Health Systems Gaps in Perinatal Care: What can be Done?

Professor, Department of Community Medicine, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

*Corresponding Author: Dr. Arun K Aggarwal, Professor, Department of Community Medicine, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India.

Received: September 16, 2017; Published: April 10, 2018

Abstract

Quantitative data shows improvement in antenatal care n terms of high first trimester registration, and better coverage of injection tetanus toxoid and distribution of tab iron and folic acid. The institutional delivery rate has improved a lot. Evidence to link higher institutional delivery with reduced perinatal mortality is also emerging. However, the quest for quantitative improvement may ignore the poor quality of care and suffering of individual cases. This paper highlights some system level gaps in terms of delayed attendance or non attendance of pregnant women and associated framework of factors contributing to this.

Keywords: Perinatal Care; Health Systems; Anaemia in Prenancy; Ultrasonography in Pregnancy

Introduction

Institutional delivery is the major strategy to address high perinatal mortality in India. In a study, hospital delivery rate and perinatal mortality rate (PNMR), reported by Sample Registration System, Registrar General of India, on a representative sample was used to calculate the correlation between the two. It was concluded that decline in perinatal rates can be attributed to India's strategic initiatives in health policy and planning for increasing deliveries in hospitals [1]. It is important to look beyond statistics into individual case stories of adverse outcomes to identify system level gaps. In this paper, we present some case studies and draw learning lessons for improvements.

Case Studies

Case Study 1: Observations at busy district hospital (DH) at district level, in a backward district, revealed that pregnant women under labor pain, were sitting on floor outside the delivery room, waiting for their turn for delivery. There was shortage of beds. Many women were sharing the hospital beds. There was shortage of many materials like cotton rolls etc. Despite these infrastructural limitations, which are common in many public sector health facilities, it was observed that there was a unique clinical protocol in place: that women reporting with labor pain are asked to get the ultrasonography examination (USG) done, before they are allowed admission to the hospital.

During daytime, this USG is available within the hospital. However, at night this facility is closed. So women are asked to go outside to nearby private USG center. Women have to make their own arrangements. Many times women with labor pain have to go on motor cycles (two wheelers) which is unsafe. It delays admission and also force families to spend out of pocket. Many a times it leads to adverse outcome. This case study shows that admissions are delayed due to 1) adherence to nonstandard protocol 2) district hospital not prepared to provide the service round the clock 3) district hospital not assuming responsibility the moment patient/ client reports to the hospital.

Case Study 2: In another case study, it was observed that a pregnant woman under labor pain was referred from a Community Health Centre (CHC) to DH due to severe anemia. DH tested the haemoglobin levels and referred back the woman to CHC with comments that woman is not severely anemic. CHC retested haemoglobin and referred back to DH with comments that she is severely anemic. DH now referred the case to the medical college hospital, where she delivered the baby at the gate of the hospital!

This raises the question of non-standardized basic investigations leading to clinical indecisiveness and adverse outcomes. Despite the fact that there is marked improvement in early antenatal registration, three antenatal checkups, Tetanus Toxoid coverage and administration of Iron and Folic Acids; still prevalence of anemia during pregnancy is rampant. Resultantly, women at term, when approach the health facility for delivery, are refused admission as they have severe anemia. They are referred from one facility to the other. Condition gets more critical when laboratory results of different facilities do not match due to substandard and unsupervised laboratory processes.

Case Study 3: In other case studies it was observed that when pregnant women with labor pain approach the health facility at Subcentre (SC), Primary Health Centre (PHC) or CHC level; staff nurses available at the facility refuse admission. This happens especially in the evening and night hours. Staff nurse send the women back after taking history and/or per vaginal examination with the comments that “there is lot of time in delivery”. Woman is asked to go back home. Many times they deliver on the way or go to private facilities. Generally, staff nurses while taking such decisions do not consult the medical officers, who are supposed to be on call duty.

This case demonstrates refusal to admit patients either due to bad attitude or lack of competence. It can also be argued that staff nurses have developed this practice as they are generally alone at night and they are not willing to take any chance during such hours. However, this is largely due to lack of protocol to call the doctors. Ultimate accountability of patient care rests with doctors. Thus, no case should be refused admission without final word from the doctor.

Case Study 4: There were many other cases, where single staff nurse on duty at PHC attempted to deliver a woman at midnight. It turned out to be complicated delivery- like breech or cord around neck and the baby was asphyxiated at birth. Now this single staff nurse is in a fix: while she is resuscitating the baby, mother is ignored on the delivery table. She also does not have the time to call the ambulance. So, after 15-20 minutes of completing initial protocols, she calls ambulance. It takes 15-30 minutes for the ambulance to come and then another 30-60 minutes to reach the district hospital. During all this process, newborn is not stabilized either before and/or during the referral and generally results in adverse outcome.

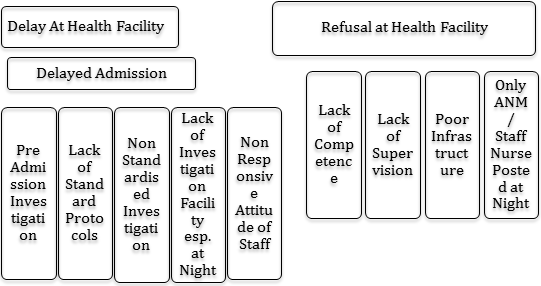

This raises fundamental questions on the policy to convert the PHC level facilities into 24 hours 7 days delivery facilities without posting sufficient staff. Any delivery room at any point of time should have minimum of two trained persons, who can manage both the mother and baby, should a complication occurs; which cannot be predicted. There should also be standard protocol that ambulance should be called immediately when the decision to deliver the mother at the health facility is taken; as complication can occur any time. No time should be wasted in shifting the mother and the baby. Lastly, there should be skill building to stabilize the baby before and during the referral. From these case studies following conceptual framework was drawn highlighting important gaps in the health systems for perinatal care:

Conceptual Framework Explaining Health System Level Gaps

Discussions

Studies worldwide have emphasized importance of quality antenatal and perinatal care. It is more important when women have some medical condition during pregnancy [2]. Studies have shown that staff posted in maternity wards are not trained on the EmONC package. Essential supplies and equipment for performing certain EmONC functions are also not available. Audits of maternal and neonatal deaths and near-misses can be used to monitor the quality of care. Authors recommended that to reduce maternal and perinatal mortality, it is essential that staff skills regarding EmONC be strengthened, the availability of supplies and equipment be increased, and that care processes be standardized in all health facilities [3].

Late arrival in hospital by women experiencing pregnancy complications was an important factor leading to maternal mortality in Nigeria. No records of Maternal/perinatal audit, that were considered important, were available. There was overall lack of appropriate data collection system in the hospitals for accurate monitoring of maternal mortality and identification of appropriate remediating actions [4]. The issue become more important as negative experiences in the health care system, can result in patient disengagement from health care in postpartum period [5].

Shortage of workforce in remote areas can be partially addressed by using the eLearning systems. E-Health presents an opportunity for improving maternal health care in underserved remote areas in low-resource settings by broadening knowledge and skills, and by connecting frontline care providers with consultants for emergency teleconsultations [6].

Conclusions

Perinatal care improvement demands learning from each and every case. Health systems should move from generic skill training to specific skill trainings critical to save newborns. All delivery points should have sufficient trained staff round the clock with readily available ambulance, irrespective of the delivery load. E technology be used for better record keeping and reporting and for skill building and monitoring. Standard operating protocols should be put in place to reduce refusal for admissions and improve quality of care. Basic laboratory tests should be validated periodically.

Acknowledgements

The above observations are from the implementation of project: Monitoring Implementation of Diarrhoea control. Acute respiratory control program, Infant death, maternal death and stillbirth review in 10 districts of Haryana. Funding was provided by National Health Mission Haryana. Contributions of Project team: Dr Dhritman Das, Dr. Anar Singh, Ms. Kiran shreon, Dr. Himani Anand for project are gratefully acknowledged.

The above observations are from the implementation of project: Monitoring Implementation of Diarrhoea control. Acute respiratory control program, Infant death, maternal death and stillbirth review in 10 districts of Haryana. Funding was provided by National Health Mission Haryana. Contributions of Project team: Dr Dhritman Das, Dr. Anar Singh, Ms. Kiran shreon, Dr. Himani Anand for project are gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Singh SK., et al. "Improving Perinatal Health: Are Indian Health Policies Progressing In The Right Direction?" Indian journal of community medicine 42.2 (2017):116-119.

- Zhang B., et al. "Association between prenatal care utilization and risk of preterm birth among Chinese women". Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology Medical sciences = Hua zhong ke ji da xue xue bao Yi xue Ying De wen ban = Huazhong keji daxue xuebao Yixue Yingdewen ban 37.4 (2017):605-611.

- Ntambue AM., et al. "Emergency obstetric and neonatal care availability, use, and quality: a cross-sectional study in the city of Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2011". BMC pregnancy and childbirth 17.1 (2017):40.

- Okonofua F., et al. "Views of senior health personnel about quality of emergency obstetric care: A qualitative study in Nigeria". PloS one 12.3 (2017): e0173414.

- Attanasio L and Kozhimannil KB. "Health Care Engagement and Follow-up After Perceived Discrimination in Maternity Care". Medical care 55.9 (2017): 830-833 .

- Nyamtema A., et al. "Introducing eHealth strategies to enhance maternal and perinatal health care in rural Tanzania".Maternal health, neonatology and perinatology 3 (2017): 3.

Citation:

Arun K Aggarwal. “Health Systems Gaps in Perinatal Care: What can be Done?” Gynaecology and Perinatology 2.2 (2018):

235-238.

Copyright: © 2018 Arun K Aggarwal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Scientia Ricerca is licensed and content of this site is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Scientia Ricerca is licensed and content of this site is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.