Case Report

Volume 1 Issue 1 - 2016

Giant Sialolith Causing Chronic Ulcer on Lateral Border of Tongue

1Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology Surendera Dental College and Research Institute, Rajasthan, India

2Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology Regional Dental College and Hospital Guwahati, Assam, India

3Department of Prosthodontics, Eklavya Dental College & Hospital, Rajasthan, India

4Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology Regional Dental College and Hospital Guwahati, Assam, India

2Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology Regional Dental College and Hospital Guwahati, Assam, India

3Department of Prosthodontics, Eklavya Dental College & Hospital, Rajasthan, India

4Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology Regional Dental College and Hospital Guwahati, Assam, India

*Corresponding Author: Suresh K. Sachdeva, Department of Oral Medicine & Radiology, Surendera Dental College & Research Institute, Rajasthan, India.

Received: September 05, 2016; Published: November 12, 2016

Abstract

Sialolithiasis is a common disease of the salivary glands, commonly affects middle-aged person with male predominance. Submandibular gland or its duct is most commonly affected. The size of salivary calculi may vary from less than 1 mm to a few cm in the largest diameter. Salivary stones that exceed 15 mm in any dimension are classified as giant. Here we present an unusual case of giant sialolith causing ulcer on lateral border of right side of tongue.

Keywords: Chronic; Giant; Sialolith; Ulcer

Introduction

Sialolithiasis is the most common disease of salivary glands, accounts for more than 50% of the salivary gland diseases. Its estimated frequency is 1.2% in the adult population with male patients affected as twice as much as female patients. [1] Most salivary calculi (80-95%) occur in the submandibular gland, whereas 5 to 20% are found in the parotid gland. The sublingual gland and minor salivary glands are rarely (1-2%) affected. Sialolithiasis can occur at any age but patients in their third to sixth decade represents most cases and it is considered rare in children. In literature, giant sialoliths are classified as those exceeding 15 mm in any one dimension or 1 g in weight. [2]

Case Report

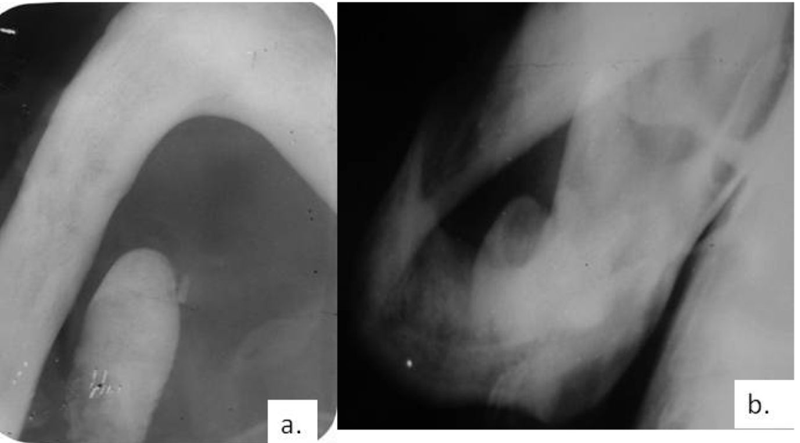

A 72-year-old man reported to the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, with the chief complaints of a nonhealing ulcer on the right lateral border of tongue since 6 months. There was no significant history of associated pain or discharge. The patient’s medical and family history was not significant. Dental history was significant for the extraction of all teeth due mobility, 5-years back. General Physical examination revealed no obvious abnormalities. Clinical examination revealed a well defined ulcer of approximate size of 2 cmX 1 cm on the right lateral border of tongue. The ulcer was firm and tender on palpation with indentation of large yellowish bony hard substance projecting from the floor of mouth (Figure-1). The surrounding mucosa appears normal in color and texture. Radiographic examination with Mandibular occlusal view revealed a well defined radio-opaque oblong mass extending from the right mandibular canine distally and apically beyond the first molar Figure-2a. Lateral oblique of mandible revealed a well-defined radiopacity in right submandibular region Figure-2b. On the basis of clinical and radiological findings, a diagnosis of right submandibular duct sialolith was made. The sialolith was excised surgically with intraoral approach under local anesthesia; the stone measured 35 millimeters (mm) and was yellowish-white in colour Figure-3. No postoperative complications were noted. Topical anesthetic and antimicrobial were advised for the ulcer, which showed signs of improvement within one week. Biochemical analysis reveals it is mainly composed of calcium, phosphate and oxalate. After 1 year follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic and salivation was satisfactory.

Figure 2a: Mandibular occlusal view showing well defined oblong radiopaque mass on right side of mandible.

Figure 2b: Lateral Oblique view showing similar radiopacity.

Figure 2b: Lateral Oblique view showing similar radiopacity.

Discussion

Sialolithiasis is a common disease of the salivary glands and a major cause of salivary gland dysfunction. Several factors seem to be involved in the development and growth of salivary calculi in the submandibular salivary gland tissue, such as wider diameter of duct, salivary flow against gravity, alkaline secretion and higher calcium and phosphate content. Fistula formation either oral or cutaneous from a salivary calculus is rare. Most cases of submandibular sialoliths are asymptomatic. Pain and swelling may be the cardinal signs and symptoms. Hypotheses regarding the pathogenesis suggest that, there is an initial organic nidus which progressively grows by the deposition of inorganic and organic substances or that intracellular micro calculi are excreted in the canal and act as a nidus for further calcification. In some cases, the existence of mucosal plugs acting as a nidus in the ductal system was reported. [3] The sialolith observed in the case was quite large, measuring approximately 35 mm and was associated with erosion of floor of mouth.

The deposition of salivary calculi is not associated with systemic diseases involving calcium metabolism. Gout seems to be the only metabolic disease that predisposes, among others, to salivary stone formation. However, the gout calculi consist typically of urate. [4] The largest sialolith reported in the literature was 70 mm in length in Wharton's duct and was described as having a "hen's egg" size. It is believed that a calculus may increase in size at the rate of approximately 1 to 1.5 mm per year. [5] Salivary calculi are usually unilateral in occurrence and round to oblong, have an irregular surface in most of the cases, vary in size from a small grain to the size of a peach pit, and are usually yellow. The stones may occur in the duct or gland, with multiple stones not uncommon. They are found more often in adults, although they also occur in children. Submandibular gland sialolith may cause pain and swelling. The pain is experienced during salivary stimulation and is intensified at mealtimes, so called “meal time syndrome”. The accumulation of saliva in the gland, duct or surrounding tissues produces swelling and the area becomes enlarged and firm. Sialoliths may present acutely as a result of acute bacterial infection secondary to stasis (sialadenitis). [6] Interestingly, this unusual similarity with the canine tooth is found to be incidental and supposed to have no significance with the management.

Diagnosis of submandibular sialolithiasis is often straightforward from a through history and examination. Plain radiographs such as occlusal view, OPG, lateral oblique view of mandible can detect opaque stones (80-95% of sialoliths). Sialography helps to visualize the whole duct system, demonstrates calculi of all sizes and also glandular damage from chronic obstruction. In some cases, the sialoliths may not be identified radiographically because the low grade of calcification or by superimposition of other hard tissue. So in those cases, advanced imaging techniques are used. Non-contrast helical CT scan with multiplanar reconstructions has become the gold standard to detect gland salivary sialoliths, especially when the sialoliths are small and poorly calcified and are not visible on standard radiographs. CT scan has the advantage of not being invasive like Sialography. Scintigraphy could be performed in the event of a suspected sialolithiasis, when Sialography is not indicated and in patients with no permeable glandular ducts. Scintigraphy is useful for the functional study of salivary glands. Scintigraphy allows for the analysis of all salivary glands at the same time. Ultrasonographic (US) examination is considered as a simple and non-invasive modality to evaluate sialoliths especially during acute infection. US examination is considered less accurate in comparison to computerized tomography (CT) in distinguishing multiple stones. It has also been reported that sialoliths smaller than 3mm may not be detected during US examination, as they will not produce acoustic shadows. [7]

Digital Sialography and subtraction Sialography have increased the sensitivity and specificity of conventional Sialography techniques that were considered gold standard. The major advantage of these newer techniques is the production of an image without the superimposition of overlying anatomical structures. The disadvantage is the need to use contrast agents that stimulates conventional Sialography. These agents may expose the patient to radiation hazards, can cause pain associated with the procedure, perforate the duct’s wall and may be contraindicated during acute infection. [8] CT Sialography has been used to delineate the ductal system of submandibular gland; this technique demonstrates the soft tissue of gland and ductal system with 3D reconstruction that avoids superimposition of anatomic structures. This technique has similar disadvantages that are seen with other Sialography techniques.

Magnetic resonance Sialography (MRS) is a new technique that is considered an excellent radiological modality for the diagnosis of sialolithiasis. MRS may be indicated in cases of acute infection where other Sialography are contraindicated since MRS does not require cannulation of the duct. Other advantages of this technique are the low radiation doses and lack of pain associated with procedure. The disadvantages of this technique include claustrophobia, cost factors, artifacts and contraindication in patients with cardiac pacemakers. Diagnostic sialadenoscopy is a newer technique in which the complete ductal system can be explored. It provides direct and reliable diagnostic information of ductal pathologies. The need for technical perfection is the only limitation of this technique. [7]

The algorithm for the treatment of sialolithiasis depends upon the size and location of sialolith. In cases of small sialoliths, conservative methods such as proper hydration of the patient, application of moist warm heat and massaging the gland in conjunction with Sialogogue can be done. Small stones can also be milked out through ductal orifices by bimanual palpation. Transoral removal is the treatment of choice for submandibular sialoliths which can be bimanually palpated and localized by ultrasonography. Sialodochoplasty can be performed to remove submandibular sialoliths which are located close to the orifice of Warthin’s duct. For large sialoliths which are located in the close proximal duct, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) can be considered. ESWL is also gaining importance because of less damage to the adjacent tissues during procedure. CO2 lasers are also gaining its popularity in the treatment of sialolithiasis because of its advantages of minimal bleeding, less scarring, clear vision and minimal postoperative complications. Submandibular gland removal is indicated only when there is a stone of substantial mass within the gland itself that is not surgically accessible intraorally and when there are small stones present in the vertical portion of Wharton’s duct from the comma area of the hilum. [8] Recent advances in optical technology have led to the development of sialoendoscopy, a new diagnostic means of directly visualizing intraductal stones which allows complete exploration of duct including shockwave lithotripsy, sialoendoscopy, interventional radiology, endoscopically video assisted transoral and cervical surgical retrieval of stones and botulinum toxin therapy. [3] However, the limitations of endoscopic techniques are adhesion of stones to the ductal walls, ducts that are too narrow, strictures, ducts with sharp angles, giant sialoliths and intraparenchymal stones. Endoscopy using wire baskets and balloons are effective alternatives to conventional surgical excision for smaller sialoliths. However, for giant sialoliths, transoral sialolithotomy with sialodochoplasty or sialadenectomy remains the mainstay of management. [9]

References

- Leung AK., et al. “Multiple sialoliths and a sialolith of unusual size in the submandibular duct: a case report”. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral Pathology Oral Radiology and Endodontology87.3 (1999): 331-333.

- Bodner L. “Giant salivary gland calculi: Diagnostic imaging and surgical management”. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral Pathology Oral Radiology & Endodontology 94.3 (2002): 320-323.

- Almasri MA. “Managementof giant intraglandular submandibular sialolith with neck fistula”. Annals of Dentistry University of Malaya 12.1 (2005): 41-45.

- Iqbal A., et al. “Unusually large sialolith of Wharton’s duct”. Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery 2.1 (2012): 70-73.

- Faye N., et al. “Imaging of salivary lithiasis”. Jornal of Radiology 87.1 (2006): 9-15.

- Nahlieli O., et al. “Pediatric sialolithiasis”. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral Pathology Oral Radiology & Endodontology 90.6 (2000): 709-712.

- Som PM and Curtin HD. “Head and Neck Imaging”. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 2003

- Yousem DM., et al. “Major Salivary Gland Imaging”. Radiology 216.1 (2000): 19-29.

- McGurk M and Renehan AG. “Controversies in the management of salivary gland disease”. Oxford University Press 2001, p 249-316.

Citation:

Suresh K. Sachdeva., et al. “Giant Sialolith Causing Chronic Ulcer on Lateral Border of Tongue”. Oral Health and Dentistry 1.1 (2016): 39-42.

Copyright: © 2016 Suresh K. Sachdeva., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Scientia Ricerca is licensed and content of this site is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Scientia Ricerca is licensed and content of this site is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.