Research Article

Volume 2 Issue 4 - 2018

The Outcome of Preoperative Administration of Single-dose Ketorolac, Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug and Placebo on Postoperative Pain in Teeth with Irreversible Pulpitis and Apical Periodontitis.

Universidad Autonoma de Baja California, 710E San Ysidro Blvd. suite “A” #1513, San Ysidro California 92173, USA

*Corresponding Author: Jorge Paredes Vieyra, Universidad Autonoma de Baja California, 710E San Ysidro Blvd. suite “A” #1513, San

Ysidro California 92173, USA.

Received: January 10, 2018; Published: January 19, 2018

Abstract

Aim: To compare the outcome of preoperative administration of single-dose ketorolac, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug and placebo on postoperative pain in teeth with irreversible pulpitis and apical periodontitis.

Methodology: A total of 54 patients (29 women and 25 men), 18 to 60 years of age with 54 eligible teeth consented to participate in the study, were divided into three groups (n = 18) according to the type of preoperative drug administrated, as follows: Group A: ketorolac 10 mg, Group B: Diclofenac Na 50 mg, and Group C: A placebo (capsule filled with sugar). The data were analyzed with chi-square, one-way ANOVA.

Results: At Days 1 and 3, preoperative administration of analgesic resulted in lower pain levels than the placebo. At Days 5 and 7, however, while preoperative administration of analgesic still resulted in less pain than the placebo, there was no significant difference between the analgesic and placebo (p= 0 .05). Ketorolac and diclofenac Na showed clinically significant relief in pain for the next three days compared with the placebo. In addition, no significant differences were demonstrated between ketorolac and diclofenac Na (Table 3).

Conclusion: A single dose of ketorolac was as effective or as safe as NSAID for the relief of pain after operations on postoperative pain in teeth with symptomatic apical periodontitis.

Introduction

Dental pain is a multifaceted process that is partially comprised of biological, biochemical, environmental, and psychogenic multi factors. Several factors can influence clinicians’ decisions to recommend analgesics in helping combat their patients’ postoperative pain. It is well recognized that, in general, preoperative pain is the principal factor in determining the level of postoperative pain (Sesle 1986). Prevention and control of pain in endodontic therapy is an important issue (Cunningham & Mullaney 1992).

Pain is conceptualized as a complex sensation and odontogenic pain is a multidimensional experience that involves sensory responses and cognitive, emotional, conceptual, cultural and motivational aspects (Sesle 1986).

The occurrence of postoperative pain of mild intensity is not an occasional event even when endodontic treatment has followed suitable standards (Arias., et al. 2013). This usually involves acute pain, meaning the correct treatment can be rapidly applied. Mild pain after chemo mechanical preparation can progress in about 10-30% of the cases (Siqueira., et al. 2002), and in most cases the patient can suffer the discomfort or can make use of common analgesics, which are usually efficient in relieving symptoms.

Development of severe pain, accompanied or not by swelling has been determined to be an unusual happening. However, these cases usually constitute a real emergency and frequently demand unscheduled visit for treatment (Pak & White 2011). Managing of postoperative pain has been the matter of many research studies, involving preoperative explanations and instructions (Sathorn., et al. 2008), long-acting anesthesia (Parirokh., et al. 2012), the glide path (Pasqualini., et al. 2012), occlusal reduction (Parirokh., et al. 2013), treatment using salicylic acid (Morse., et al. 1990), non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Attar., et al. 2008), combination of ibuprofen and acetaminophen (Menhinick., et al. 2004), narcotic analgesics (Ryan., et al. 2008), a combination of narcotic analgesics with aspirin (Morse., et al. 1987) or acetaminophen (Sadeghein., et al. 1999), and steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Pochapski., et al. 2009).

Pain perception is a highly idiosyncratic and variable occurrence moderated by multiple physical and psychological aspects, and pain reporting is influenced by factors other than the experimental process (Bender 2000). The extrusion of microbes or debris during endodontic therapy ends in inflammatory reaction and inflammation (Oliveira., et al. 2011). A latest systematic evaluation revealed that among 3% and 58% of patients were reported to have experienced endodontic postoperative pain (Sathorn., et al. 2008).

Stimulation of nociceptive nerve fibers may also be related to concentrations of inflammatory mediators like histamine (Dale & Richards 1918). Also, histamine, is capable of sensitizing and activating nociceptive nerve fibers (Hargreaves., et al. 1994). Managing of pain is a serious part of medicine and dentistry, as pain is a main postoperative symptom after numerous dental procedures. There are various analgesics and procedures; patients want the best for control their pain, and clinicians need to know them. Knowing how well an analgesic and procedure works and its associated adverse effects is essential to clinical decision-making (Cunningham & Mullaney 1992).

The occurrence and severity of postoperative pain are related with specific dental proedures; the highest is with root canal therapy (Levine., et al. 2006). Post-endodontic pain, especially after primary endodontic therapy, should ideally be eliminated by the treatment; however, analgesics are frequently required to reduce pain (Cunningham & Mullaney 1992). There is a solid association among pulp status and postoperative pain, influencing the capability of pain, which may undermine the patient’s confidence in the procedure and the clinician (Arias., et al. 2013). Ketorolac is an excellent acting analgesic used widely in surgery and medicine (Grond & Sablotzki 2004).

In dentistry, there have been numerous studies that used a single dose of ketorolac associated with tramadol for control of pain mainly in operations on the third molars. However, its analgesic efficacy is controversial, with reports that its effect is similar (Mishra & Khan 2012) or less good (Desjardins., et al. 1998) that of non-steroidal anti- inflammatory drugs (NSAID). According to these findings a single dose of tramadol has some relatively usual unfavorable effects (Shah., et al. 2013). The purpose of this study was to compare the outcome of preoperative administration of single-dose ketorolac, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug and placebo on postoperative pain in teeth with irreversible pulpitis and apical periodontitis.

Materials and Methods

The institutional review board of the Facultad de Odontología Tijuana México approved the study protocol and all the participants were treated in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (www.cirp.org/library/ethics/helsinki). The study started in August 2016 and ended in August 2017. The main inclusion criteria were: a) A diagnosis of pulpitis confirmed by positive response to hot and cold tests and b) Clinical and radiographic evidence of symptomatic apical periodontitis. It was determined based on the clinical symptoms severe preoperative pain (VAS > 60) and severe percussion pain (VAS > 60). Confirmed by positive response to hot and cold tests. Thermal pulp testing was performed by the author, and radiographic interpretation was verified by one certified oral surgeon.

Patient selection

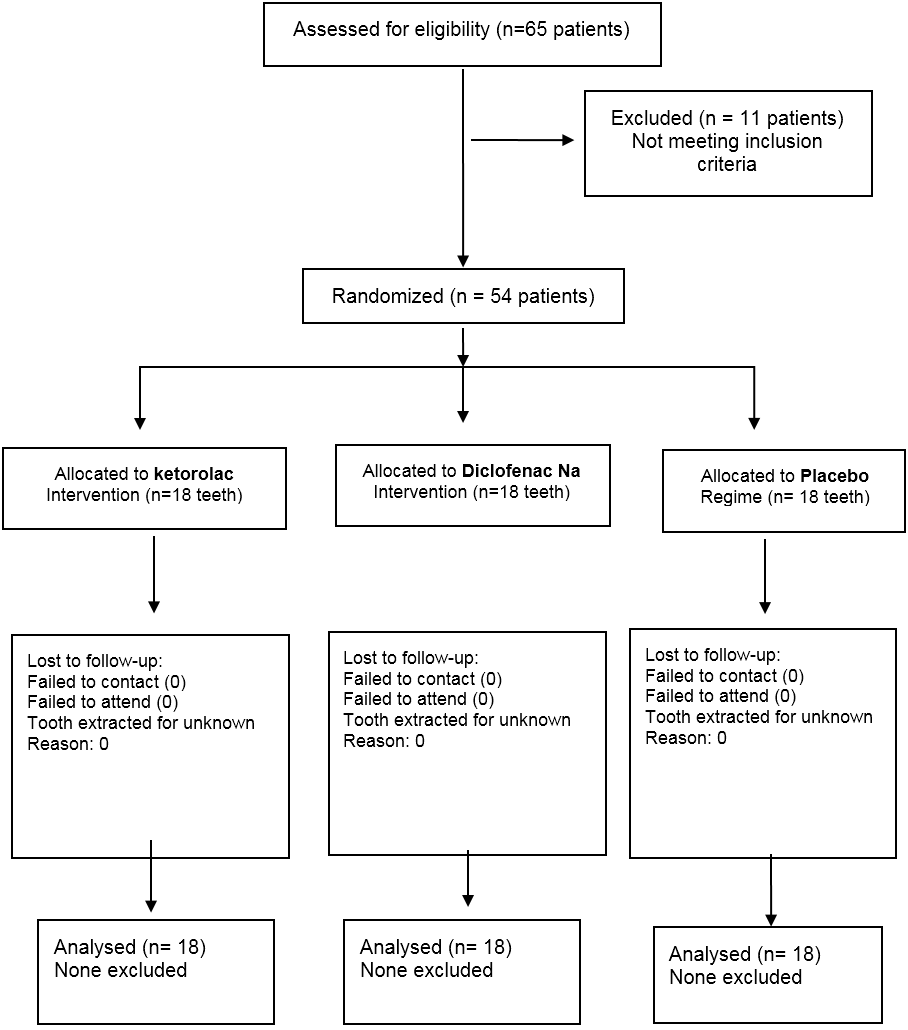

Fifty-four of sixty-five patients (29 women and 25 men), 18 to 60 years of age with 54 eligible teeth consented to participate in the study. The study design is shown in Figure 1. The patients were randomly divided into three groups using a web program. The patient number and group number were recorded. Informed consent was obtained from each patient and the possible discomforts and risks were fully explained.

Fifty-four of sixty-five patients (29 women and 25 men), 18 to 60 years of age with 54 eligible teeth consented to participate in the study. The study design is shown in Figure 1. The patients were randomly divided into three groups using a web program. The patient number and group number were recorded. Informed consent was obtained from each patient and the possible discomforts and risks were fully explained.

A total of 54 patients were divided into three groups (n = 18) according to the type of preoperative drug administrated, as follows: Group A: ketorolac 10 mg (Siegfried Rhein S.A. de C.V, Mexico,DF), Group B: Diclofenac Na 50 mg (Voltaren, Novartis Mexico), and Group C: A placebo (capsule filled with sugar).

A registered pharmacist compounded identical-appearing capsules of the ketorolac, Diclofenac Na and the placebo (opaque yellow size ‘‘0’’ capsules). All medications were placed in identical bottles so that they were indistinguishable to the investigator.

The administration of drugs and root canal treatment were performed by two different researchers. One assistant knew the allocation and the drug type in the capsules, but the operator and the patient did not know which drug type was administered.

Patient selection was based on the following criteria: 1) The aims and requirements of the study were freely accepted; 2) Treatment was limited to patients in good health; 3) Patients with symptomatic or asymptomatic teeth with vital pulps and apical periodontitis; 4) A positive response to hot and cold pulp sensitivity tests; 5) Presence of sufficient coronal tooth structure for rubber dam isolation; 6) No prior endodontic treatment on the involved tooth and 7) No analgesics or antibiotics were used five days before the clinical procedures began.

Exclusion criteria included the following: 1) Patients who did not meet inclusion requirements; 2) Patients who did not provide authorization for participation; 3) Patients who were younger than 16 years old; 4) Patients who were pregnant; 5) Patients who were diabetic; 6) Patients with a positive history of antibiotic use within the past month; 7) Patients whose tooth had been previously accessed or endodontically treated; 8) Teeth with root resorption, and 9) Immature/open apex, or a root canal in which patency of the apical foramen could not be established were all excluded from the study. Teeth with periodontal pockets deeper than 4 mm, or the presence of a periapical radiolucency more than 2 cm diameter also were excluded of the study.

Also excluded were patients whose affected tooth and related work had any of the following issues: curved canals, problems in determining working length, broken files, over-instrumentation, and over or incomplete filling.

Once eligibility was confirmed, the study was explained to the patient by the authors, and the patient was invited to participate. After explaining the clinical procedures and risks and clarifying all questions raised, each patient signed a written informed consent form and was randomly assigned to either the three groups by using a block of random numbers generated by one of the investigators. A medical history was obtained and a clinical examination performed. All teeth were 11 asymptomatic and 43 symptomatic with a diagnosis of pulpitis determined by hot and cold sensitivity tests and radiographically all teeth showed a small and irregular radiolucency at the tooth apex (Schick Technologies, Long Island City, NY, USA). The diagnostic findings were checked by comparing the tooth’s response against that of an adjacent tooth with a vital pulp. Periodontal probing revealed no increased probing depth (> 3 mm) around any of the teeth. The author performed all the clinical procedures.

Treatment protocol

All treatment sessions were approximately 50 minutes in length to allow for acceptable time for completion of treatment in one visit. The author performed all the clinical procedures. The standard procedure for the three groups included local anesthesia with 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine (Septodont Saint-Maur des Fossés, France) and rubber dam isolation the tooth was disinfected with 2.5% NaOCl (Ultra bleach, Bentonville, AR, USA).

All treatment sessions were approximately 50 minutes in length to allow for acceptable time for completion of treatment in one visit. The author performed all the clinical procedures. The standard procedure for the three groups included local anesthesia with 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine (Septodont Saint-Maur des Fossés, France) and rubber dam isolation the tooth was disinfected with 2.5% NaOCl (Ultra bleach, Bentonville, AR, USA).

Infected dentine was completely removed and endodontic access cavities prepared with sterile high-speed carbide burs #331 (SS White. Lakewood, NJ, USA). After gaining access, the canals were explored with #06, #08, and #10 K-type hand files (Flex-R files, Moyco/Union Broach, York PA, USA) according to the initial diameter of the foramen, its degree of flattening, and its canal curvature using a watch-winding motion.

Working Length (WL) was established by introducing a #10 K-file up to the apical foramen as determined by a Root ZX (J Morita, Irvine, CA, USA). The WL was confirmed radiographically (Schick Technologies, Long Island City, NY, USA).

The root canals were negotiated and enlarged with hand instruments (Flex-R files, Moyco/Union Broach, York PA, USA) until reaching an ISO size #20 at WL. The coronal portions of the root canals were flared with sizes 2-3 Gates-Glidden burs (Dentsply Maillefer). Irrigation with 2mL 2.5% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) was performed using a 24-G needle (Max-I-Probe; Dentsply Tulsa Dental, York, PA) during access and a 31-G NaviTip needle (Ultradent Products Inc., South Jordan, UT) when reaching the WL after each file insertion. Reciprocating files (VDW, Munich Germany) were used to complete root canal preparation. 17% EDTA (Roth International Ltd, Chicago, IL, USA) served as a lubricant.

All Reciprocating files were driven by an electric micro motor with limited torque (VDW Silver Reciproc Motor, VDW). R25 files (25.08) were used in narrow and curved canals, and R40 files (40.06) were used in large canals. Three in-and-out (pecking) motions were applied with stroke lengths not exceeding 3 mm in the cervical, middle, and apical thirds until attaining the established WL. All the files were used in only 1 tooth (single use) and then discarded. Patency of the apical foramen was maintained during all the techniques by introducing a #10 K-type file at WL. The preparations for all the groups were finished using a #45 file for narrow or curved canals and a #60 file for wide canals.

After completion of instrumentation, all root canals were irrigated with 2.5 mL 17% EDTA for 30 seconds followed by a final irrigation with 5.0 mL 5.25% NaOCl using the EndoVac irrigation system (Discus Dental, Culver City, CA, USA).

The root canals were dried with sterile paper points and obturated at the same appointment using lateral condensation of gutta-percha and Sealapex sealer (SybronEndo). Access cavities of anterior teeth were etched and restored with Fuji IX (GC Corp, Tokyo, Japan). For posterior teeth, a buildup restoration was placed using the same etching technique and Fuji IX.

After concluding the endodontic treatment procedure, all patients were given postoperative advices to take analgesics (400 mg ibuprofen) in the event of pain at a dosage of 1 tablet every 6 hours. The level of discomfort was valued as follows: no pain; mild pain, which was recognizable but not discomforting; moderate pain, which was discomforting but bearable (analgesics, if used, were effective in relieving pain); flare-up, which was difficult to bear (analgesics, if used, were ineffective in relieving pain). Cases with severe postoperative pain and/or the occurrence of swelling were categorized as flare-ups and treated accordingly (Table 2). After completion of RCT, patients were instructed to return to their referring dentist for definitive restoration as soon as possible.

Patients were contacted by telephone by the clinical assistant after 24 hours, 48 hours, 72 hours, and 7 days and asked to provide the following information: their perceived pain score and whether they had taken the analgesic medication prescribed and, if so, the quantity of tablets and the number of days needed to control the pain. All the patients were instructed to contact the clinic or the dentist in charge of their treatment if the analgesic medication failed to provide pain release or in the event of any other type of emergency.

The Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test was applied to compare the incidence of postoperative pain. The level of significance adopted was 5% (p = 0.05).

The final scale was as follows:

None: 0-6.0, Faint: > 6.0-17.0, Weak: > 17.0-27.0, Mild: > 27.0-42.3, Moderate: > 42.3-60.3, Strong: > 60.3-74.7, Intense: > 74.7-90.6 and Maximum: > 90.6–100.

None: 0-6.0, Faint: > 6.0-17.0, Weak: > 17.0-27.0, Mild: > 27.0-42.3, Moderate: > 42.3-60.3, Strong: > 60.3-74.7, Intense: > 74.7-90.6 and Maximum: > 90.6–100.

Results

A summary of the study can be seen in the flow diagram (Figure 1). There were no statistically significant differences among the groups in terms of demographic data (Table 1) or pulp and periapical status (Table 2) (P > .05). Ketorolac and diclofenac Na showed clinically significant relief in pain for the next three days compared with the placebo group. In addition, no significant differences were demonstrated between ketorolac and diclofenac Na (Table 3).

| (n) | Ketorolac/tramadol | Diclofenac Na | Placebo | |

| 30.69 ±7.35 | 28.12 ± 5.99 | 31.87 ±7.35 | ||

| Gender | Age | |||

| Male | 25 | 8 | 9 | 8 |

| Female | 29 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| Tooth Number | ||||

| Tooth 3 | 13 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Tooth 14 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Tooth 18 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Tooth 29 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Tooth 13 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Tooth 7 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Total: 54 | 18 | 18 | 18 | |

P = 0.05

Table 1: Demographic data.

Table 1: Demographic data.

| (n) Ketorolac Diclofenac Na | Placebo | ||||

| Pulp Status | |||||

| Vital | 54 | 18 | 18 | 18 | |

| Periapical Status | |||||

| Score | 1 | 44 | 16 | 14 | 14 |

| Score | 2 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Presence of: | |||||

| Preoperative palpation | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Preoperative swelling | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Preoperative Sinus Tract | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Postoperative palpation | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Postoperative swelling | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Postoperative sinus tract | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

P = 0.05

Table 2: Pulp and peri apical status of teeth and postoperative pain.

Table 2: Pulp and peri apical status of teeth and postoperative pain.

| Ketorolac | Diclofenac Na | Placebo | |

| Preoperative percussion | 13 (I) | 15 (I) | 14 (I) |

| Preoperative pain | 16 (I) | 15 (I) | 12 (I) |

| Postoperative | |||

| One-day pain | 1 (M) | 3 (M) | 7 (I) |

| Postoperative | |||

| Two-day pain | 0 (W) | 1 (W) | 4 (Mi) |

| Postoperative | |||

| Three-day pain | 0 (N) | 0 (F) | 1 (F) |

P = 0.05

Table 3: Pain levels according to the groups.

Scale: I: Intense, M: moderate, Mi: Mild, W: Weak, F: Faint and N: None

Table 3: Pain levels according to the groups.

Scale: I: Intense, M: moderate, Mi: Mild, W: Weak, F: Faint and N: None

Similarly, there were no significant differences among the groups in terms of preoperative pain levels and percussion pain levels, but there was a difference in post-operative pain in placebo group. Results from this study indicated that pre-operative pain with the diagnoses of irreversible pulpitis with apical periodontitis were the most common for respondents to choose analgesics to relieve their patients’ pain.

A total of 7 patients needed analgesics postoperatively: five of these were in the placebo group, one in the ketorolac group, and one in the diclofenac Na group. Table 3 shows lower pain levels in all groups.

In the present study, two patients experienced a flare-up. Two cases of flare-up were from the placebo group. Both required an intra-appointment visit. The flare-up from the patient in the placebo group showed no signs of swelling, but caused extreme pain. Upon opening the tooth, inflammatory drainage was established.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the outcome of preoperative administration of single-dose ketorolac, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug and placebo on postoperative pain in teeth with irreversible pulpitis and apical periodontitis. Practice background was significant for analgesic preferences relating to severe pain with an endodontic diagnosis of irreversible pulpitis with acute periradicular periodontitis (Gatewood., et al. 1990). Our findings agree with Nusstein (Nusstein & Beck 2003) relating to prescribe analgesic in teeth with irreversible pulpitis and symptomatic apical periodontitis.

Many local and systemic factors such as age, gender, general health, group of teeth, pulp and periapical status, and occlusal contacts, amongst others, may interact and modulate the occurrence of pain of endodontic origin (Hargreaves., et al. 2011).

Know those factors as predictors may contribute to define preventive oral health strategies to manage this undesirable condition, minimizing pain incidence and/or intensity and reducing patient suffering at the individual and population levels. Additionally, clinicians may use this information to advise patients about pain outcomes related to RCT (Law., et al. 2015).

The results of the present study indicated that some clinicians were more likely to choose medication before and after endodontic treatment to manage this painful clinical scenario, whereas other educators and residents were much more likely to prescribe combination drugs in addition to instrumentation (Litkowski., et al. 2005).

Prescribe a drug before start root canal in patients with irreversible pulpitis will reduce postoperative pain or sensitivity.

The results from this present study are consistent with the findings of Law (Law., et al. 2015) that to avoid severe postoperative pain in endodontic therapy, preemptive analgesia strategies before initiation of treatment are necessary and with Krasner and Jackson (Krasner & Jackson 1986) who noted from their study that although pulpectomy eliminates endodontic pain, postoperative pain and discomfort.

Two previous investigations have reported that the prophylactic use of analgesics at the end of the treatment visit had a positive influence on postoperative pain felt by the patients (Morse., et al. 1990, Mehrvarzfar., et al. 2012). Therefore, in the present study, all patients were instructed to take the first dose of the drug fifteen minutes before start the treatment visit. Considering the multifactorial nature of preoperative pain and postoperative pain, prevention and treatment strategies should depend on the identification and management of key predisposing factors (Arias., et al. 2013, Ng., et al. 2011).

Pain intensity is therefore influenced by various factors, including environmental, previous experience, mental health and attitude making it a challenge to measure. Numerous scales have been used for pain intensity evaluation. Of these, the numerical rating scale (NRS), which is a scale with end points of the extremes of no pain and as bad as it could be or the worst pain. There is also the visual rating scale (VRS), which is made up of a list of descriptors that represent the level of pain intensity. It is subjective, and its association with disease may be indirect; however, it is a personal qualitative judgment of patients’ perception of pain strength (Pasqualini., et al. 2012).

In this study were used the visual analogue scale (VAS) that is a 10-cm line arrangement that relates to verbal parameters. Although it’s value as a measurement is well-documented and another form to evaluate the response of the patients’ pain to the analgesics. To show the real amount/perception of postoperative pain felt by patients, it appears to be reasonable for researchers to provide two evaluation forms: one to include the conventional VAS and another form to evaluate the response of the patients’ pain to the analgesics (Lund., et al. 2005, Lara-Munoz., et al. 2004).

Additionally, visual analogue scales (VAS) and numeric rating scales (NRS) for assessment of pain intensity agree well, are equally sensitive in assessing acute pain, and are superior to a four-point verbal categorical rating scale (Breivik., et al. 2008). Hence, in the present study, patients were given one such form, and the results showed that some patients reported severe pain that was unbearable and not interfered with the patient’s daily activities with no significant difference between the groups A and B.

Our findings agree with Wells (Wells., et al. 2011). That reported the presenting initial moderate pain level is representative of emergency patients with symptomatic teeth, a pulpal diagnosis of necrosis, and a periapical radiolucency. Postoperative pain or sensitivity is often used to assess the quality of analgesics because of its consistency and intensity.

Pre-operative examination, interpretation of symptoms and diagnosis are crucial factors in long-term success of endodontic therapy. No controversies exist regarding the fact that teeth diagnosed with irreversible pulpitis should be treated in one session, if no technical complications arise (Paredes-Vieyra & Enriquez 2012). However, in cases of pulp necrosis with or without periradicular periodontitis the literature is more controversial. Although preoperative administration of analgesics has been found to be effective in reducing postoperative pain (Law., et al. 2015), there has been various studies related to the effect of the preoperative administration of antihistamines on postoperative pain.

Wells (38) found that there were decreases in postoperative pain levels with the preoperative administration use of ibuprofen, a finding in harmony with ours. The decreased pain levels in the analgesic group can be explained by the ability of analgesic to eliminate pain resulting in blocking of nociceptive sensory nerve fibers (Dale & Richards 1918, Hargreaves., et al. 1994).

An interesting finding in the present study was that while the preoperative administration of ketorolac resulted in less pain than that of a diclofenac Na there was no significant difference between ketorolac and diclofenac Na administration. This finding suggests that the preoperative administration of ketorolac as a single dose before the treatment is beneficial in reducing postoperative pain. Pain of endodontic origin depends on the multidimensional interrelationship between host, pulp and periapical tissues, and the nature of endodontic procedures. The measurement of pain intensity is a reasonable way to evaluate treatment efficacy.

The authors deny any conflict of interests related to this study.

Conclusion

A single dose of ketorolac was as effective or as safe as NSAID for the relief of pain after operations on postoperative pain in teeth with symptomatic apical periodontitis.

References

- Arias A., et al. “Predictive models of pain following root canal treatment: a prospective clinical study”. International Endodontic Journal 46.8 (2013): 784-793.

- Attar S., et al. “Evaluation of Pretreatment Analgesia and Endodontic Treatment for Postoperative Endodontic Pain”. Journal of Endodontics 34.6 (2008): 652-655.

- Bender IB. “Pulpal pain diagnosis. A review”. Journal of Endodontics 26.3 (2000): 175-179.

- Breivik H., et al. “Assessment of pain”. British Journal of Anaesthesia101.1 (2008): 17-24.

- Cunningham CJ and Mullaney TP. “Pain control in endodontics”. Dental Clinics of North America 362 (1992) 393-408.

- Dale HH and Richards AN. “The vasodilator action of histamine and of some other substances”. Journal of Physiology 52.2-3 (1918): 110-165.

- Desjardins PJ., et al. Bromfenac, a non-opioid analgesic, compared with tramadol and placebo for the management of postoperative pain. Clinical Drug Investigation 15.3 (1998): 177-185.

- Gatewood RS., et al. “Treatment of the endodontic emergency: a decade later”. Journal of Endodontics 16.6 (1990): 284-291.

- Grond S and Sablotzki A. “Clinical pharmacology of tramadol”. Clinical Pharmacology 43.13 (2004): 879-923.

- Hargreaves KM., et al. Cohen’s Pathways of the Pulp, 10th edition. St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby Elsevier (2011).

- Hargreaves KM., et al. “Pharmacology of peripheral neuropeptide and inflammatory mediator release”. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology 78.4 (1994): 503-510.

- KrasnerP and Jackson E. “Management of post treatment endodontic pain with oraldexa-methasone: a double-blind study”. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral Pathology 62.2 (1986): 187-190.

- Lara-Munoz C., et al. “Comparison of three rating scales for measuring subjective phenomena in clinical research: I use of experimentally controlled auditory stimuli”. Archives of Medical Research 35.1 (2004): 43-48.

- Law AS., et al. “Predicting severe pain after root canal therapy in the National Dental PBRN”. Journal of Dental Research 94.3S (2015): 37S-43S.

- Levin L., et al. “Post-operative pain and use of analgesic agents following various dental procedures”. American Journal Dental 19.4 (2006): 245-247.

- Litkowski LJ., et al. “Analgesic efficacy and tolerability of oxycodone 5 mg/Ibuprofen 400 mg compared with those of oxycodone 5 mg/acetaminophen 325 mg and hydrocodone 7.5 mg/acetaminophen 500 mg in patients with moderate to severe postoperative pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-dose, parallel-group study in a dental pain model”. Clinical Therapeutics 27.4 (2005): 418-429.

- Lund I., et al. “Lack of interchangeability between visual analogue and verbal rating pain scales: a cross sectional description of pain etiology groups”. BMC Medical Research Methodology 5 (2005): 5-31.

- Mehrvarzfar P., et al. “Effects of three oral analgesics on post- operative pain following root canal preparation: a controlled clinical trial”. International Endodontic Journal 45.1 (2012): 76-82.

- Menhinick KA., et al. “The efficacy of pain control following nonsurgical root canal treatment using ibuprofen or a combination of ibuprofen and acetaminophen in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study”. International Endodontic Journal 37.8 (2004): 531-541.

- Mishra H and Khan FA. “A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized comparison of pre-and postoperative administration of ketorolac and tramadol for dental extraction pain”. Journal of Anesthesiology and Clinical Pharmacology 28.2 (2012): 221-225.

- Morse DR., et al. “Comparison of prophylactic and on-demand diflunisal for pain management of patients having one-visit endodontic therapy”. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology 69.6 (1990): 729-736.

- Morse DR., et al. “Comparison of diflunisal and an aspirin-codeine combination in the management of patients having one-visit endodontic therapy”. Clinical Therapeutics9.5 (1987): 500-511.

- Ng YL., et al. “A prospective study of the factors affecting outcomes of nonsurgical root canal treatment: part 1: periapical health”. International Endodontic Journal 44.7 (2011): 583-609.

- Nusstein JM and Beck M. “Comparison of preoperative pain and medication use in emergency patients presenting with irreversible pulpitis or teeth with necrotic pulps”. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral Pathology Oral Radiology and Endodontics 96 (2003): 207-214.

- Oliveira SM., et al. “Involvement of mast cells in a mouse model of postoperative pain”. European Journal of Pharmacology672.1-3 (2011): 88-95.

- Pak JG and White SN. “Pain Prevalence and Severity before, during, and after Root Canal Treatment: A Systematic Review”. Journal of Endodontics 37.4 (2011): 429-438.

- Paredes-Vieyra J and Enriquez FJ. “Success rate of single-versus two-visit root canal treatment of teeth with apical periodontitis: a randomized controlled trial”. Journal of Endodontics 38.9 (2012): 1164-1169.

- Parirokh M., et al. “Effect of occlusal reduction on postoperative pain in teeth with irreversible pulpitis and mild tenderness to percussion”. Journal of Endodontics 39.1 (2013): 1-5.

- Parirokh M., et al. “Effect of bupivacaine on postoperative pain for inferior alveolar nerve block anesthesia after single-visit root canal treatment in teeth with irreversible pulpitis”. Journal of Endodontics 38 (2012): 1035-1039.

- Pasqualini D., et al. “Postoperative Pain after Manual and Mechanical Glide Path: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Endodontics 38.1 (2012): 32-36.

- Pochapski MT., et al. “Sydney GB Effect of pretreatment dexamethasone on postendodontic pain”. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology 108.5 (2009): 790-795.

- Rosenberg PA., et al. “Leung A The effect of occlusal reduction on pain after endodontic instrumentation”. Journal of Endodontics24.7 (1998): 492-496.

- Ryan JL., et al. “Gender Differences in Analgesia for Endodontic Pain”. Journal of Endodontics 34.5 (2008): 552-556.

- Sadeghein A., et al. “A comparison of ketorolac tromethamine and acetaminophen codeine in the management of acute apical periodontitis”. Journal of Endodontics 25.4 (1999): 257-259.

- Sathorn C., et al. “The prevalence of postoperative pain and flare-up in single- and multiple-visit endodontic treatment: a systematic review”. International Endodontic Journal 41.2 (2008): 91-99.

- Sessle BJ. “Recent developments in pain research: central mechanisms of orofacial pain and its control”. Journal of Endodontics 12.10 (1986): 435-44.

- Shah AV., et al. “Comparative evaluation of pre-emptive analgesic efficacy of intramuscular ketorolac versus tramadol following third molar surgery”. Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery 12.2 (2013): 197-202.

- Siqueira JF., et al. “Incidence of postoperative pain after intracanal procedures based on an antimicrobial strategy”. Journal of Endodontics 28.6 (2002): 457-460.

- Wells LK., et al. “Efficacy of ibuprofen and ibuprofen/acetaminophen on postoperative pain in symptomatic patients with a pulpal diagnosis of necrosis”. Journal of Endodontics 37.12 (2011): 1608-1612.

Citation:

Jorge Paredes Vieyra., et al. “The Outcome of Preoperative Administration of Single-dose Ketorolac, Non-steroidal Antiinflammatory

Drug and Placebo on Postoperative Pain in Teeth with Irreversible Pulpitis and Apical Periodontitis.”. Oral Health and

Dentistry 2.4 (2018): 410-420.

Copyright: © 2018 Jorge Paredes Vieyra., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Scientia Ricerca is licensed and content of this site is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Scientia Ricerca is licensed and content of this site is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.