Research Article

Volume 1 Issue 2 - 2017

Integrating Eye Health Care within the Public Health System: A Case Study of the Kiri Vong Referral Hospital Vision Centre, Takeo Province, Cambodia

1Faculty of Education, Lifestyle Research Centre, Avondale College of Higher Education, Cooranbong, NSW, Australia

2Population Health Unit, Centre for Eye Research Australia (CERA), Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital, East Melbourne, The University of Melbourne, Australia

3CARITAS Takeo Eye Hospital, Takeo Province, Cambodia

4CBM

5National Program for Eye Health, Preah Ang Duong Hospital, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

6LV Prasad Eye Institute, Hyderabad, India

2Population Health Unit, Centre for Eye Research Australia (CERA), Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital, East Melbourne, The University of Melbourne, Australia

3CARITAS Takeo Eye Hospital, Takeo Province, Cambodia

4CBM

5National Program for Eye Health, Preah Ang Duong Hospital, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

6LV Prasad Eye Institute, Hyderabad, India

*Corresponding Author: Gail M Ormsby, Faculty of Education, Business and Science and Lifestyle Research Centre, Avondale College

of Higher Education, Cooranbong, NSW, Australia.

Received: May 13, 2017; Published: June 13, 2017

Abstract

Purpose: Integrated community eye health services remain a challenge in low-income countries. We report outcomes of a new district level Vision Centre (VC) providing refraction and primary eye care.

Design: A retrospective, non-randomised, multiple method case study.

Materials and Methods: Data were derived from VC and eye hospital records for the commencement of the VC (2010 to 2012). The new Eye Health Strategic Program Planning and Evaluation Framework and the WHO Health Systems Six Pillars were used as the summative evaluation framework. Themes included: social determinants, service delivery, detection of vision impairment, customers, coverage and utilisation of services, quality, awareness raising, leadership and governance, workforce, accessibility, health information, cost recovery, networks and linkages, advocacy, health systems integration, outcomes and impact. A semi-structured questionnaire tool was used to interview staff, community leaders and patients.

Results: Outreach screenings and eye health promotion influenced individuals to seek eye care. Of the 7,858 consultations (between May 2010 to October 2012) were conducted by two ophthalmic nurses at the VC, and 2,802 refractions were performed with an average of 90 refractions per month. Of those refracted, 73% (n = 2,037) required glasses and of whom, 54% (n = 1,090) were dispensed as ready-made glasses. The cost recovery mechanism of the VC contributed to the overall salaries of the district hospital and the purchase of new supplies. The district hospital administrators reported a 6-10% increase in the number of out-patients visiting the hospital.

Conclusion: Collaborative planning, training, mentorship, improved private-public partnerships resulted in an integrated VC in a district hospital.

Introduction

The challenge of VISION 2020 is to eliminate avoidable blindness through affordable, achievable and appropriate measures. However,

a vast number of people in low- and middle-income countries do not have access to comprehensive eye health services. Different

community ophthalmology approaches need to be tested and evaluated to improve the reach to the community but the interface with

community medicine cannot be ignored. Thus, the development of public health strategies to address avoidable blindness needs to

embrace the field to community medicine and community ophthalmology. Strategies for diagnosis and treatment/clinical practice of

eye diseases/conditions cannot be designed without giving thought to the wider mobilisation of community education and promotion

of eye health, rehabilitation for individuals with low vision and incurable blindness, and improved communication and coordination

of activities between departments/organisations. For example, the medical/health/wellbeing issues associated with diabetes/diabetic

retinopathy demonstrate the need for new innovations and initiatives to be integrated/targeted at the community level. The provision

of refraction services in remote/un-serviced locations needs further field testing, since evidence-based information about the integration

of eye health into primary health care is limited [1-3].

The Global Burden of Disease report emphasises the burden of avoidable blindness and refractive error as leading causes of vision impairment. [4-5] There is interest in how eye health care services (including refraction correction) could be introduced and strengthened at the district level health system particularly for neglected communities in low resource countries. [6-11] Du Toit., et al. declared: “evidence of integration of eye health into primary health care is currently weak…Documentation and evaluation of existing projects are required…”. [12] The literature shows there is a lack of definition as to what integration really means and there is insufficient research about how best to approach this strategy, and even less evidence pertaining to the integration of eye health. [13,14] There is compelling evidence that the integration of eye health services into health systems should be revisioned, innovative innovations require testing and analysis particularly for low- and middle-income countries to address universal health coverage. [1,8,12-16]

In India, where many rural regions lack eye health care services, the LV Prasad Eye Institute (LVPEI) (a not-for-profit organization) introduced a Pyramid Model which incorporated the Vision Center (VC) as a facility to provide primary eye health care for poorly serviced communities. [17,18] The VC is managed by a Vision Technician, a high school graduate who has received one year of technical training. The tasks they perform include: early identification of potential vision-threatening disease such as cataract and uncorrected error, prescription and dispensing of affordable spectacles and the treatment of minor eye problems. People requiring further treatment or eye surgery are referred to the secondary eye care centre.

In 2007, the Australian Government funded a number of non-government organisations (NGOs) as part of the Avoidable Blindness Initiative (ABI) that was launched to reduce avoidable blindness in South-east Asia and the Western-Pacific region based upon LVPEI Model. [19] Cambodia, a lower middle-income country, has made improvement in rebuilding its health system. [20] Its public health system is organised around the district health model that serves approximately 100,000 to 200,000 people. [21] The national 2007 Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness (RAAB) of people over 50 years of age, showed that while cataract was the primary cause of bilateral blindness (74%), uncorrected refractive error was the main cause of bilateral vision impairment (52.8%). [22,23] Refraction correction with the provision of glasses is considered an intervention that can be introduced at the community level, but currently refraction services are only available in some provincial eye units.

This article reports on the establishment of a VC during 2009/2010, at the government public health Kiri Vong District Referral Hospital (KVDRH), where primary eye care and refraction correction were introduced to service the remote rural population.

Methods

The research followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was provided by the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear

Hospital, Human Research and Ethics Committee Australia, the Cambodian National Ethics Committee for Health Research, and by the

Provincial and District Departments of Health. Informed written informed consent was obtained from all respondents.

Study Setting

The KVDRH is located in the southern plains of Takeo Province. The district consists of 12 communes and has a population of 97,711. [21] During 2005-2007, the Swiss Red Cross worked closely with the KVDRH staff to strengthen the hospital operational systems and staff capacity. [24,25] In 2008, the KVDRH was assessed to be suitable to implementation of a pilot demonstration VC within the district health system, being planned by CBM Australia, the CARITAS Takeo Eye Hospital (CTEH), the District Health Department and KVDRH administrators/staff. The VC opened in April 2010 as a sub-system within the hospital.

The KVDRH is located in the southern plains of Takeo Province. The district consists of 12 communes and has a population of 97,711. [21] During 2005-2007, the Swiss Red Cross worked closely with the KVDRH staff to strengthen the hospital operational systems and staff capacity. [24,25] In 2008, the KVDRH was assessed to be suitable to implementation of a pilot demonstration VC within the district health system, being planned by CBM Australia, the CARITAS Takeo Eye Hospital (CTEH), the District Health Department and KVDRH administrators/staff. The VC opened in April 2010 as a sub-system within the hospital.

The CTEH, located 35 kms north of Kiri Vong, functions as a regional provincial eye hospital and training facility for ophthalmic nurses and resident ophthalmologists, in collaboration with the University of Cambodia and the National Program for Eye Health. The CTEH was well resourced to guide and monitor the establishment of the VC.

During the set-up of the VC, the equipment was purchased following the guidelines of VISION2020 [Table 1].

| Essential equipment | Available and functional |

Desirable equipment | Available and functional |

Ideal equipment | Available and functional |

| Flash light | √ | Tonometer | √ | Lea symbols | √ |

| Distance Vision charts | √ | Slit lamp | √ | Low vision testing kit | √ |

| Near vision charts | √ | Auto refractor | √ | Glucometer | √ |

| Trial set | √ | Colour vision chart | √ | Standardised medical records software | × |

| Trial frames | √ | Blood pressure instrument | √ | Retinal camera | × |

| Paediatric trial frames | √ | Thermometer | √ | ||

| Slit lamp with application tonometer | √ | Telephone/ Mobile phone | √ | ||

| Streak retinoscope | √ | Computer | √ | ||

| Direct ophthalmoscope | √ | ||||

| Hand washing solutions | √ | ||||

| Generator | √ | ||||

| Lensometer | √ | ||||

| Occluder | √ | ||||

| Near vision light | √ | ||||

| Big mirror | √ | ||||

| Optical rule | √ | ||||

| Cross cylinder | √ | ||||

| Medical record books | √ | ||||

Table 1: Table of ophthalmic equipment for the Kiri Vong District Referral Hospital Vision Centre.

The CTEH provided the initial training, technical guidance, monitoring and supervision for the ophthalmic nurses over the two-year set-up period. Since no specific operational guidelines exist for VC in Cambodia, specific roles and responsibilities were developed by CTEH in consultation with the KVDRH and the National Program for Eye Health [Table 2].

|

Table 2: The roles and responsibilities of the ophthalmic nurses at the Kiri Vong District Referral Hospital Vision Centre.

Conducting an Eye Health Knowledge, Attitude and Practice (EH-KAP) Survey: During the establishment of the VC, a population-based survey (n = 599) was conducted in 2010 to assess the knowledge of eye health among communities in three operational districts (Dunkeo, Kiri Vong and Bati) in Takeo Province. A total of 30 clusters were randomly selected with 20 people per cluster. Details are published elsewhere. [26] The purpose of this process was to gain a clearer understanding about the knowledge, beliefs and attitudes toward eye health practices and why many individuals who had been screened did not seek eye health care services. [27]

End of project evaluation process: A case study approach [28] utilising multiple methods, [27] was adopted to conduct the end-of-project evaluation in December 2012 by two evaluators from the Centre for Eye Research Australia (CERA).

An initial semi-structured questionnaire tool was developed in consultation with CBM Australia to guide the interview process. The selection of outcomes in the questionnaire was guided by the key themes of the WHO Six Building Blocks (WHO), [28] and a newly developed Eye Health Strategic Planning and Evaluation Framework. [1] The interview themes included: 1) social determinants of eye health, 2) service delivery systems, 3) facility operation systems, 4) networks, linkages, and 5) outcomes and 6) impact. The interview tools were adapted for two target groups: 1) for the eye health staff, health department leaders and community leaders and 2) for patients. The themes included in the evaluation process followed the items shown in Table 3.

| Social determinant indicators |

|

| Service delivery systems indicators |

|

| Operation systems indicators |

|

| Networks and linkages indicators |

|

| Outcomes indicators |

|

| Impact indicators |

|

Code: *RAAB = Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness

Table 3: The key domains and the range of indicators assessed during the evaluation process.

Table 3: The key domains and the range of indicators assessed during the evaluation process.

The evaluation interview tools were translated into Khmer in Australia by a translation consultancy firm and then checked in Cambodia for content validity and accuracy with experienced Khmer consultants. The evaluation was conducted at two main sites: the KVDRHVC and at the CTEH. Key stakeholders included VC staff, KVDRH administrators, the district health department leaders, health centre staff, community leaders, patients and staff at CTEH associated with the set-up and monitoring of the VC. Interviews were conducted by the evaluators with the assistance of a Khmer researcher.

Twelve patients were purposively interviewed about their experience visiting the VC. The evaluators (GO and MS, with experience in public health and optometry respectively) could observe the procedures conducted by VC staff as they assessed incoming patients, provided eye health advice, recorded patient data, conducted eye examinations and conducted refraction. Quantitative data (e.g. the number of patients receiving refraction) were obtained from KVRHVC and the CTEH records for the period April 2010 to November 2012.

Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness (RAAB) Survey: A RAAB Survey (n = 4,650; 179 non-respondents) was conducted in January 2012 among individuals ≥ 50 years of age in Takeo Province. Visual acuity using Snellen tumbling E-chart was measured. Lens status in each eye was assessed by an ophthalmologist using a direct ophthalmoscope. Details are published elsewhere. [31]

Statistical Methods

Data were recorded and tabulated using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington USA) and then exported and analysed using SPSS Statistics Version 20 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) for Windows and Stata version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). The qualitative data were reviewed manually to identify common themes.

Data were recorded and tabulated using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington USA) and then exported and analysed using SPSS Statistics Version 20 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) for Windows and Stata version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). The qualitative data were reviewed manually to identify common themes.

Results

The VC staffed by two ophthalmic nurses, is located in the front of the hospital next to the out-patient services. The primary purpose of the VC was to provide accessible, affordable integrated primary eye care services, including initial detection of eye diseases, visual acuity testing and refraction, simple treatment including the distribution of ready-made glasses, and referral to the eye hospital if needed.

strong>1. Social determinants of eye health

The EH-KAP population-based survey (n = 599) was conducted to assess the knowledge of eye health among communities. [26] The results showed that literacy and knowledge were limited in the region. Of the Kiri Vong respondents, 9.5% (57/599) reported they had never attended school and only 5.3% (32/599) had attended secondary school. The level of eye health knowledge was significantly low. Overall, while 85% of the respondents (n = 509) they had ‘heard’ of cataract, only 19% listed surgery as the best treatment.

The EH-KAP population-based survey (n = 599) was conducted to assess the knowledge of eye health among communities. [26] The results showed that literacy and knowledge were limited in the region. Of the Kiri Vong respondents, 9.5% (57/599) reported they had never attended school and only 5.3% (32/599) had attended secondary school. The level of eye health knowledge was significantly low. Overall, while 85% of the respondents (n = 509) they had ‘heard’ of cataract, only 19% listed surgery as the best treatment.

Of the total respondents 23.7% (142/599), only 9.2% (13/142) from Kiri Vong reported they had an eye examination (p = < 0.001). Based upon the findings, project staff reported that increased efforts focused upon the provision of eye health promotion messages at different avenues including: radio, outreach screenings, training of health centre staff and consultation with patients.

strong>2. Service delivery systems

Eye disease detection and control

The two ophthalmic nurses are responsible for examining patients who come to the VC. This includes the initial registration of the patient, taking the patient history and the examination of patient’s eyes. Patients who require further treatment such as cataract surgery are referred to the CTEH. Primary eye care treatment and refraction is performed and if patients require additional medical assistance they are referred to the hospital’s out-patient department.

Eye disease detection and control

The two ophthalmic nurses are responsible for examining patients who come to the VC. This includes the initial registration of the patient, taking the patient history and the examination of patient’s eyes. Patients who require further treatment such as cataract surgery are referred to the CTEH. Primary eye care treatment and refraction is performed and if patients require additional medical assistance they are referred to the hospital’s out-patient department.

VC Customers

The KVDRH draws patients from a 25 km radius. The patients were interviewed about their perspectives of the eye health services. Most patients interviewed reported they had heard of the VC through the village health workers and by word of mouth from other patients.

The KVDRH draws patients from a 25 km radius. The patients were interviewed about their perspectives of the eye health services. Most patients interviewed reported they had heard of the VC through the village health workers and by word of mouth from other patients.

“I heard from the village volunteer. They said, if we have mild eye problems or needed glasses, we could go to KVDRH, but for serious eye problems that need to be ‘peeled’, then go to CTEH”. Male, 55 yrs.

Most customers pay a service fee of 2,000-4,000 Rs (approximately $ USD 0.5-1). Spectacles are available for around $ 3 to $ 10. In Cambodia, no specific study of the patients’ willingness to pay for spectacles has been conducted. However, we found that some individuals declared they could not afford to purchase spectacles: “I have a centless pocket”.

Coverage and utilisation

VC staff liaise with village health workers to arrange outreach screening activities, and to create awareness of the VC services. During May 2010 to October 2012, a total of 3,499 patients were screened in the Kiri Vong district. Of these people, 14% were reported to have ‘normal eyes’, 39% had cataract, 15% had refractive error. Four patients were recorded to have glaucoma. Of those patients referred from the village screening session to the VC, 40% (n = 92) attended the VC.

VC staff liaise with village health workers to arrange outreach screening activities, and to create awareness of the VC services. During May 2010 to October 2012, a total of 3,499 patients were screened in the Kiri Vong district. Of these people, 14% were reported to have ‘normal eyes’, 39% had cataract, 15% had refractive error. Four patients were recorded to have glaucoma. Of those patients referred from the village screening session to the VC, 40% (n = 92) attended the VC.

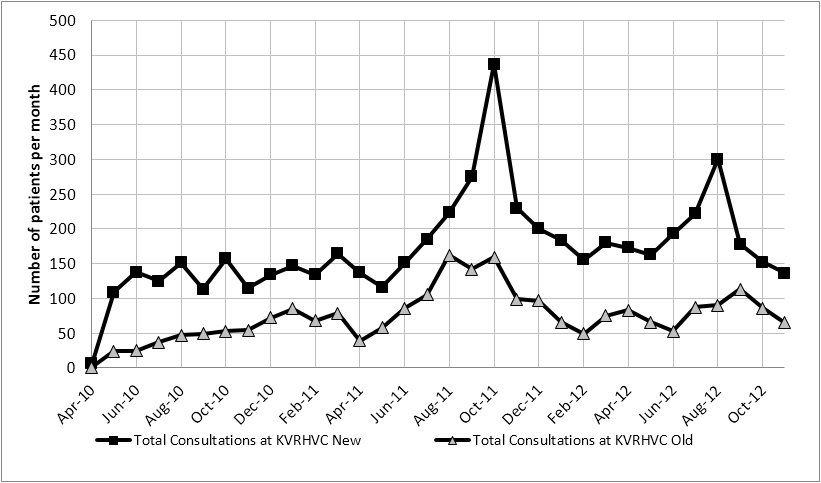

Monthly consultations ranged from 7 at the commencement of the service in 2010 to 596 in the month of October 2011 [Figure 1]. Excluding the results for October 2011, the mean number of consultations per month was 234. The noted surge in consultations in October 2011 coincides with the World Sight Day community promotion, when consultations were provided free of charge. The total consultations performed at the VC during this period time were 7,858 of which, 69.8% were new patients to the KVDRH and 30.2% were follow-up consultations.

Figure 1: Total monthly consultations at the Kiri Vong District Referral Hospital Vision

Centre Between April 2010 to November 2012.

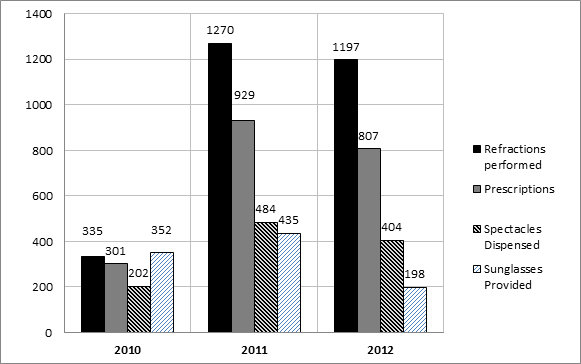

For this same period, 2,802 refractions were performed at the VC. Of those refracted, 73% (n = 2,037) required prescriptions for spectacles. For patients who required spectacles, 54% (n = 1,090) were dispensed the ready-made glasses [Figure 2].

Figure 2: Numbers of refractions, prescriptions, spectacles dispensed, and sunglasses

dispensed at the Vision Centre from May 2010 to November 2012.

At the KVDRH only 4% (n = 26) of the total consultations conducted at the VC during 2011 were children. Of this group, 65% (n = 16) were female. Between 2010 and 2012, of the 303 children diagnosed with cataract at CTEH outpatient clinic, 48% (n = 146) underwent surgery (compared to 60%, n = 6,665 adults with cataract). For this same time period at CTEH, spectacles were provided for 71% (n = 551) of the 772 children for refractive error. Across all ages, 4,242 spectacles were made/dispensed from the optical workshop at the CTEH.

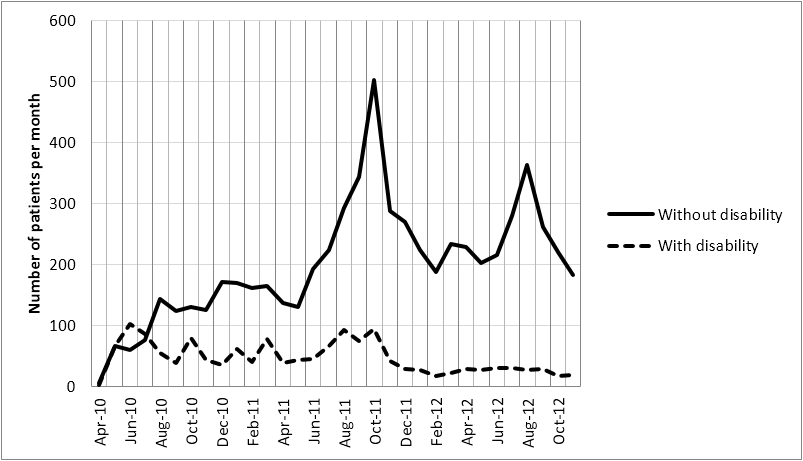

The identification of people with disability who are able to access eye health services is one method to document changes in equity and inclusion. [32] In this project, self-reported disability was recorded. Since 2010, the VC at the KVDRH provided services to 1,490 (19%) patients with non-vision related self-reported disability [Figure 3].

Figure 3: Trend of attendance per month of patients at the Kiri Vong District Referral Hospital

Vision Centre outpatient, comparing patients with and without self-reported disability.

Quality

The quality of the services was monitored in two main ways. Firstly, the Optical Technician was assessed for quality by an external Australia consultant optometrist during November 2010, and again in December 2013. Secondly, the CTEH does periodic checks on routines at the KVDRHCV. The records were checked for the quality of reporting patient information.

The quality of the services was monitored in two main ways. Firstly, the Optical Technician was assessed for quality by an external Australia consultant optometrist during November 2010, and again in December 2013. Secondly, the CTEH does periodic checks on routines at the KVDRHCV. The records were checked for the quality of reporting patient information.

The services of the VC were positively supported by the District Health Department: “We do not hear any criticism from the public about the eye service from this VC”.

Awareness raising and eye health promotion

Short presentations regarding eye health are delivered to patients and their families during waiting times on a daily basis at the CTEH and KVDRHVC. Additionally, presentations are made at each of the outreach screening sessions held at Health Centres. Pamphlets and posters (in English and Khmer) depicting different common eye conditions were prepared by CTEH during the project period. These were used for specific counselling of patients and community outreach as a means to inform mainly literate people. In collaboration with the National Program for Eye Health (NPEH) and the Fred Hollows Foundation, radio spots were scripted and broadcast to inform communities. Further promotion was organised for World Sight Day, where messages were sent to Health Centres and the community regarding the availability of no-cost treatment for the day. The change in attendance during October is noted [Figure 1].

Short presentations regarding eye health are delivered to patients and their families during waiting times on a daily basis at the CTEH and KVDRHVC. Additionally, presentations are made at each of the outreach screening sessions held at Health Centres. Pamphlets and posters (in English and Khmer) depicting different common eye conditions were prepared by CTEH during the project period. These were used for specific counselling of patients and community outreach as a means to inform mainly literate people. In collaboration with the National Program for Eye Health (NPEH) and the Fred Hollows Foundation, radio spots were scripted and broadcast to inform communities. Further promotion was organised for World Sight Day, where messages were sent to Health Centres and the community regarding the availability of no-cost treatment for the day. The change in attendance during October is noted [Figure 1].

Staff of the VC reinforced the importance of promoting the services of the VC to attach people to have their eyes checked: “People are hearing from former eye patients, VC staff, CDMD [Cambodian Development Mission for Disability], and NGOs. Some people are hearing from the radio spot”.

Patients reported how they shared information with others.

Patients reported how they shared information with others.

“Yes [I would tell others]. There were 2-3 students at my school that had the same eye problem as me. The [students] came to get their eyes checked”. Male, 19 yrs.

“I know many people will go to get their eyes checked if the outreach team comes to the village. They see I got healed with eye treatment”. Female, 66 yrs.

3. Operation systems

Leadership and governance

The day to day operation of the VC is managed by two ophthalmic nurses with overall leadership provided by the hospital administration. During the establishment and operation of the VC, technical support, monitoring and mentoring was provided on a monthly basis by the CTEH team but the overall management has been transitioned to the administration of KVDRH. However, VC staff can easily contact CTEH by phone if further technical assistance is required.

Leadership and governance

The day to day operation of the VC is managed by two ophthalmic nurses with overall leadership provided by the hospital administration. During the establishment and operation of the VC, technical support, monitoring and mentoring was provided on a monthly basis by the CTEH team but the overall management has been transitioned to the administration of KVDRH. However, VC staff can easily contact CTEH by phone if further technical assistance is required.

The sustained performance of the KVDRH can largely be attributed to the strength of governance and the stakeholder (local district health department/hospital administration and NGO) contributions. All patient data are recorded. The finances can be monitored by checking the patient payment receipts against the patient data logbook. The money paid for fees and glasses are receipted by the hospital cashier.

Infrastructure, equipment and medicines

The KVDRH provided a wheel-chair accessible renovated room next to the out-patient department at the front of the hospital where there is a covered waiting area. The VC is well signed and easily visible to people. Equipment to check visual acuity and to conduct refraction was provided through the CTEH funded by the ABI program. The KVRHVC has a complete inventory of ‘essential’ and ‘desirable’ equipment as suggested by VISION 2020 (Table 1). Basic eye medicines are provided by the hospital.

The KVDRH provided a wheel-chair accessible renovated room next to the out-patient department at the front of the hospital where there is a covered waiting area. The VC is well signed and easily visible to people. Equipment to check visual acuity and to conduct refraction was provided through the CTEH funded by the ABI program. The KVRHVC has a complete inventory of ‘essential’ and ‘desirable’ equipment as suggested by VISION 2020 (Table 1). Basic eye medicines are provided by the hospital.

While logistics support for the VC can play a critical role in the delivery of quality eye health care, the procedures were still being defined. The procurement of supplies was conducted in consultation with the hospital.

Human resources

Two ophthalmic nurses were recruited as local residents selected from the KVDRH to help ensure that they would remain long-term. One ophthalmic nurse received three months of focused refraction technician training that was facilitated in Phnom Penh by the Brien Holden Vision Institute in collaboration with the National Eye Health Program. A spectacle technician was trained (three months) for CTEH and provides the back-up refraction services for VC, including making customized spectacles.

Two ophthalmic nurses were recruited as local residents selected from the KVDRH to help ensure that they would remain long-term. One ophthalmic nurse received three months of focused refraction technician training that was facilitated in Phnom Penh by the Brien Holden Vision Institute in collaboration with the National Eye Health Program. A spectacle technician was trained (three months) for CTEH and provides the back-up refraction services for VC, including making customized spectacles.

The CTEH provided initial training, technical guidance, monitoring and supervision for the two-year period. Since no specific operational guidelines exist for VC in Cambodia, specific roles and responsibilities were developed by CTEH in consultation with the KVDRH and the NPEH [Table 4].

|

Table 4: The roles and responsibilities of the ophthalmic nurses at the Kiri Vong

District Referral Hospital Vision Centre.

As part of the services, the ophthalmic nurse is able to perform eye irrigation, suture removal, foreign body removal and refraction. During outreach screening sessions, the primary function of the examination is to diagnose and refer for cataract surgery. Diagnoses other than cataract or refractive error, such as ptergyium and eye infection, are recorded on the field report. However, the details other than cataract or refractive error were not recorded in the computerised reports.

Health Centre staff had been provided two sessions of primary eye care training. The staff that were interviewed reported that the primary eye care training was very beneficial, and they were able to now refer patients to the VC for further primary eye care assistance namely for refraction services.

Health information system

The VC established an information system and from the evaluators’ observations, all patient details were manually recorded in a logbook as a backup system and to counter electricity outages. Summary information was transferred to a computerised database for reporting purposes. Patients attending the VC are provided with a unique identification number for their medical record. Standard recorded information includes: name, address, age, gender, socio-economic status and of self-reported disability. Data entry occurs at the time of the patient registration and computer entries were done at the end of the day. However, there are no well-established linking procedures to enable accurate recording from periodic assessments of the same patient. There no well-established linking procedures to enable accurate recording from periodic assessment of the same patient. Details of all diagnosis is not reported in the computerised system but could be achieved if required by the health department.

The VC established an information system and from the evaluators’ observations, all patient details were manually recorded in a logbook as a backup system and to counter electricity outages. Summary information was transferred to a computerised database for reporting purposes. Patients attending the VC are provided with a unique identification number for their medical record. Standard recorded information includes: name, address, age, gender, socio-economic status and of self-reported disability. Data entry occurs at the time of the patient registration and computer entries were done at the end of the day. However, there are no well-established linking procedures to enable accurate recording from periodic assessments of the same patient. There no well-established linking procedures to enable accurate recording from periodic assessment of the same patient. Details of all diagnosis is not reported in the computerised system but could be achieved if required by the health department.

Cost recovery and finance management

Cost recovery from the sale of glasses at the VC makes a positive contribution to the income of the KVDRH. It currently supports the cost of two salaries and provides a sustainable supply of glasses. “Since 2010, the income has increased…The income from consultation, selling glasses and services are [contributing] to the general hospital revenue…the general income of the hospital is increasing 5-6%”.

Cost recovery from the sale of glasses at the VC makes a positive contribution to the income of the KVDRH. It currently supports the cost of two salaries and provides a sustainable supply of glasses. “Since 2010, the income has increased…The income from consultation, selling glasses and services are [contributing] to the general hospital revenue…the general income of the hospital is increasing 5-6%”.

Within the region approximately 30% of the population is below the poverty line (Hospital Administrator). There are some patients who cannot afford the total cost of eye care and glasses, and therefore receive some subsidy through the hospital and some of the patients decided not to purchase spectacles.

There were limited records regarding out-of-pocket expenditure for patients, and there was insufficient time to manually check all records. The KVDRHVC accepts a nominal user fee from patients who cannot cover the full cost of their care. Data from 2011 showed that of the 484 spectacles dispensed at the VC, 34% (n = 163) of patients issued free spectacles, and 66% (n = 321) of individuals paid out-of-pocket expenditure within a range of US $ 3-5.

4. Networks and linkages

Various networks and linkages have become well established including: between the Health Centres and the district and provincial hospitals and the VC.

Various networks and linkages have become well established including: between the Health Centres and the district and provincial hospitals and the VC.

Other backup health services and technical support

The CTEH which operates as the regional eye hospital, is a major tertiary ophthalmic facility performing multiple roles in the provision of eye care for Cambodia. The 2011 NPEH Annual Report, stated that 191,741 outpatient department examinations were performed in Cambodia. Of the total, 15% (n = 28,964) were conducted at Takeo. Additionally, of the 22,762 cataract surgeries performed nationally, 10.5% (n = 2,400) were performed at Takeo. Since 2009 to October 2012, the CTEH performed 11,802 refractions and dispensed 6,419 spectacles through the hospital’s optical workshop. The CTEH performs an integral role in the provision of services for all patients referred from the VC and outreach screenings. [21,23]

The CTEH which operates as the regional eye hospital, is a major tertiary ophthalmic facility performing multiple roles in the provision of eye care for Cambodia. The 2011 NPEH Annual Report, stated that 191,741 outpatient department examinations were performed in Cambodia. Of the total, 15% (n = 28,964) were conducted at Takeo. Additionally, of the 22,762 cataract surgeries performed nationally, 10.5% (n = 2,400) were performed at Takeo. Since 2009 to October 2012, the CTEH performed 11,802 refractions and dispensed 6,419 spectacles through the hospital’s optical workshop. The CTEH performs an integral role in the provision of services for all patients referred from the VC and outreach screenings. [21,23]

Referral systems

During the period, referrals from the Kiri Vong Operational District accounted for 5% of the total outpatient consultations at the CTEH. Between 2010 to 2012, on average, 65 patients per month or a total of 1,774 patients were referred from the KVDRHVC consultation and outreach screening process to the CTEH. Cataract accounted for 47% (n = 826) of the patients, 44% (n = 788) ‘other’ conditions, 8% (n = 153) refractive error, and < 1% (n = 7) for glaucoma.

During the period, referrals from the Kiri Vong Operational District accounted for 5% of the total outpatient consultations at the CTEH. Between 2010 to 2012, on average, 65 patients per month or a total of 1,774 patients were referred from the KVDRHVC consultation and outreach screening process to the CTEH. Cataract accounted for 47% (n = 826) of the patients, 44% (n = 788) ‘other’ conditions, 8% (n = 153) refractive error, and < 1% (n = 7) for glaucoma.

The use of community outreach interventions was an important means to promote the eye care services within the community. One to three outreach interventions were conducted per month in collaboration with the CTEH to recruit, diagnose and refer people with cataract or serious eye problems. The typical screening team consisted of an ophthalmic nurse, a general nurse from the Health Centre and a community-based rehabilitation (CBR) and a staff member from the Cambodian Development Mission for Disability (CDMD). Occasionally a community ophthalmologist from CTEH accompanies the team.

Remote communities (Health Centres) are notified in advance of the scheduled screening day with a letter, radio spots and brochures. A week before the scheduled event, the screening site is visited and eye health promotion banner is displayed. For the screening directly coordinated by the VC, the ophthalmic nurse performs the vision screening and eye examinations. The data sourced from the VC records (May 2010 to October 2011) showed that of the 2,997 people screened, 39% had cataract and 15% had refractive error.

Referral linkages had been established between the Health Centres and VC, as well between CDMD and CTEH. During the evaluation, some patients at the VC were observed to have a referral form from CDMD and a Health Centre.

Community-based rehabilitation support

During the ABI program, CBM and CTEH worked to strengthen avenues to improve inclusion of people with disabilities. [26] Planned advocacy efforts resulted in disability inclusion being adopted as part of the national primary eye care curriculum from 2011. The provision of low vision services at CTEH extended the services for those people with severe vision impairment. Close working collaboration with schools has improved access for children with disabilities into specialist or mainstream education. Close working relations were developed with the local community-based rehabilitation organisation, CDMD. During 2012, 132 (87 females) patients were referred by CDMD and 134 (74 females) patients were referred from the Health Centres to the VC. A two-way referral pathway helped to develop more effective referral systems.

During the ABI program, CBM and CTEH worked to strengthen avenues to improve inclusion of people with disabilities. [26] Planned advocacy efforts resulted in disability inclusion being adopted as part of the national primary eye care curriculum from 2011. The provision of low vision services at CTEH extended the services for those people with severe vision impairment. Close working collaboration with schools has improved access for children with disabilities into specialist or mainstream education. Close working relations were developed with the local community-based rehabilitation organisation, CDMD. During 2012, 132 (87 females) patients were referred by CDMD and 134 (74 females) patients were referred from the Health Centres to the VC. A two-way referral pathway helped to develop more effective referral systems.

Advocacy

Considerable work had been achieved by CTEH to influence the national government to make adjustments to the primary eye care training curriculum to include information about the principles of disability inclusion. At the local level, the KVDRH administrators had been successful in influencing the provincial health department to include some budget allocation for eye health care in the next financial year.

Considerable work had been achieved by CTEH to influence the national government to make adjustments to the primary eye care training curriculum to include information about the principles of disability inclusion. At the local level, the KVDRH administrators had been successful in influencing the provincial health department to include some budget allocation for eye health care in the next financial year.

5. Outcomes

Eye disease detection and control

Conducting outreach screening, particularly in remote communities, is an initial step in the early detection of eye diseases. The strengthening of the referral systems resulted in the increased number of patients attending the VC or the eye hospital for diagnosis and treatment. Simple ophthalmic procedures and the provision of refraction testing at the VC improved the distribution of spectacles. However, one concern noted was the challenge of referring patients to CTEH for customized glasses. In the longer-term it would be anticipated that a spectacle workshop could be introduced at KVRDH.

Eye disease detection and control

Conducting outreach screening, particularly in remote communities, is an initial step in the early detection of eye diseases. The strengthening of the referral systems resulted in the increased number of patients attending the VC or the eye hospital for diagnosis and treatment. Simple ophthalmic procedures and the provision of refraction testing at the VC improved the distribution of spectacles. However, one concern noted was the challenge of referring patients to CTEH for customized glasses. In the longer-term it would be anticipated that a spectacle workshop could be introduced at KVRDH.

In comparison with the stand-a-lone VC sites in India, the KVDRHVC presented as an appropriate efficient and effective facility locates in a prominent position at the front of the hospital. The KVDRHVC was staffed by two four-year trained ophthalmic nurses (three years training as a general nurse, one-year training as an ophthalmic nurse and three months training in refraction), compared to a one-year trained vision technician in the Indian VC. The provision of refraction services and the diagnosis of an array of eye diseases resulted in the early detection of eye problems, onsite treatment of simple issues and referral of patients requiring further treatment at the CTEH.

Accessibility

The provision of VC district eye health care service demonstrated the improved number of people accessing the eye health services. Ongoing monitoring and evaluation will continue to inform the evidence about its sustainability. There is preliminary evidence to show that regularly monitored linkages and networks have been established among the Health Centres and the VC as well as CTEH. The evidence of referrals to and from CDMD, assisting people with disability to access services, has been positively received with regular updates and discussions informing the referral system.

The provision of VC district eye health care service demonstrated the improved number of people accessing the eye health services. Ongoing monitoring and evaluation will continue to inform the evidence about its sustainability. There is preliminary evidence to show that regularly monitored linkages and networks have been established among the Health Centres and the VC as well as CTEH. The evidence of referrals to and from CDMD, assisting people with disability to access services, has been positively received with regular updates and discussions informing the referral system.

Affordability

The current cost recovery mechanism has resulted in savings. The VC has been able to purchase additional supplies from its own funds. Provision for poor patients requiring spectacles has been made possible. The provision and sale of sunglasses ($ 5-10) has provided additional income to subsidise other costs. The interviews with patients revealed that there were concerns about their ability to pay for all costs associated with acquiring glasses. Given that the community is largely engaged in subsistence farming, ongoing monitoring of patients’ ability to pay for spectacles is recommended. The recruitment of patients through awareness is critical as a feeder mechanism long-term.

The current cost recovery mechanism has resulted in savings. The VC has been able to purchase additional supplies from its own funds. Provision for poor patients requiring spectacles has been made possible. The provision and sale of sunglasses ($ 5-10) has provided additional income to subsidise other costs. The interviews with patients revealed that there were concerns about their ability to pay for all costs associated with acquiring glasses. Given that the community is largely engaged in subsistence farming, ongoing monitoring of patients’ ability to pay for spectacles is recommended. The recruitment of patients through awareness is critical as a feeder mechanism long-term.

Satisfaction with services

The interviews were conducted with 12 patients (8 female) who had attended the VC and had acquired glasses, to check the level of satisfaction of patients. Ages ranged between 19-78 years. Patients discussed themes including: concerns about cost, quality of the spectacles, colour and style. While all patients reported they would encourage other people go to check their eyes at the VC, 10 people said they were satisfied with their glasses. The selected comments illustrate patients’ responses.

The interviews were conducted with 12 patients (8 female) who had attended the VC and had acquired glasses, to check the level of satisfaction of patients. Ages ranged between 19-78 years. Patients discussed themes including: concerns about cost, quality of the spectacles, colour and style. While all patients reported they would encourage other people go to check their eyes at the VC, 10 people said they were satisfied with their glasses. The selected comments illustrate patients’ responses.

“I can see clearly. Takes away the glare. I can work under the sun. I can see the road clearly”. Male, 55 yrs.

“I love it [the glasses] because it helps see things clearly. To go anywhere, I bring it along all the time. It is small and easy to put in the pocket”. Male, 55 yrs.

Sustainability

The sustainability of the KVDRHVC was demonstrated through the integration of the eye health care services as part of the public health system. The positive results of establishing the VC at the district level was supported by the District/Hospital Administration: “The VC assists with the income to the hospital…it is a hospital with multiple services, and as a results, the number of patients is increasing. Even although the Australian funds have been removed, the eye service activity is still running quite well”.

The sustainability of the KVDRHVC was demonstrated through the integration of the eye health care services as part of the public health system. The positive results of establishing the VC at the district level was supported by the District/Hospital Administration: “The VC assists with the income to the hospital…it is a hospital with multiple services, and as a results, the number of patients is increasing. Even although the Australian funds have been removed, the eye service activity is still running quite well”.

6. Impact

Prevalence of blindness and vision impairment

Results of the RAAB showed that the main cause of blindness in individuals (presenting VA < 3/60) was un-operated cataract (81.8%), and the population weighted prevalence (presenting bilateral blindness < 3/60) was 3.4%. Even although the cataract surgical coverage (CSC) had increased during recent years, there remains a ‘stagnant prevalence of blindness’ attributed to the changing age structure of the population. [26]

Prevalence of blindness and vision impairment

Results of the RAAB showed that the main cause of blindness in individuals (presenting VA < 3/60) was un-operated cataract (81.8%), and the population weighted prevalence (presenting bilateral blindness < 3/60) was 3.4%. Even although the cataract surgical coverage (CSC) had increased during recent years, there remains a ‘stagnant prevalence of blindness’ attributed to the changing age structure of the population. [26]

Cataract surgical coverage in the bilaterally blind was 64.7% (female 59.5%, male 78.1%). The cataract surgical outcome was good in 88.7% (best-corrected visual acuity ≥ 6/18) of eyes operated in the last 5 years, and poor (best-corrected visual acuity < 6/60) in only 7.7%. Refractive error accounted for 65.1% (n = 521; < 6/18-6/60) of vision impairment. [26]

Equity and inclusion

Confluent with WHO policy, all people have the right to be able to access eye health care services. During this reported period, 1,490 people with self-reported disability (in addition to vision impairment) accessed the VC services, demonstrating that improved equity and inclusion was being achieved. [27]

Confluent with WHO policy, all people have the right to be able to access eye health care services. During this reported period, 1,490 people with self-reported disability (in addition to vision impairment) accessed the VC services, demonstrating that improved equity and inclusion was being achieved. [27]

Eye health seeking behaviour

The total consultations performed at the new VC during this period time were 7,858. More than half of the patients had never received an eye examination. The increased number of new patients seeking an eye check-up at the VC and at CTEH is an early indication of improved eye health seeking behaviour.

The total consultations performed at the new VC during this period time were 7,858. More than half of the patients had never received an eye examination. The increased number of new patients seeking an eye check-up at the VC and at CTEH is an early indication of improved eye health seeking behaviour.

Vision and quality of life

Patients’ improved vision and quality of life is best expressed by the patients’ testimonials:

“It [the glasses] helped me to see the medium letters and I could see clearly. Now I am able to read the newspaper, watch the video. Before, I could not do it. With farm work, I can see the grass and it is very easy for me to cut or dig the land”. Male, 52 yrs.

Patients’ improved vision and quality of life is best expressed by the patients’ testimonials:

“It [the glasses] helped me to see the medium letters and I could see clearly. Now I am able to read the newspaper, watch the video. Before, I could not do it. With farm work, I can see the grass and it is very easy for me to cut or dig the land”. Male, 52 yrs.

“I feel happy because I can do farm work again”. Female, 55 yrs.

A positive outcome reported by the hospital administrative staff and the district health department, was that the overall out-patient numbers for the district hospital had increased between 6-10% during the period since the establishment of the VC. Increased community promotion of eye health care services, radio spots and the onsite visibility of the VC are suggested to have contributed to this change. The initial issues that were considered and addressed during the preliminary planning and early implementation phase are shown, along with the relevant areas of: ‘service delivery’, ‘operation systems’, ‘networks and linkages’, ‘outcomes’ and ‘impact’ [Table 5]. This illustration promotes the importance and relevance of considering both clinical and community medicine/ophthalmology inter-related strategies throughout the planning process.

| Situation Analysis 2009 | Determinants of Service Accessibility 2009 | Service Delivery Systems 2009 | Operation Systems | Networks and Linkages | Outcomes 2012 | Impact 2012 |

Eye disease prevalence

|

Individual health status

|

Eye disease detection and control

|

Leadership and Governance

|

Back-up support

|

Eye disease detection and control Current services provided:

|

Eye disease prevalence

|

Government Eye Health Policies and Guidelines

|

Social and cultural Determinants

|

Coverage and Utilisation

|

Infrastructure

|

Referral and Linkage Systems

|

Equity and Inclusion

|

Endorsement of human rights, equity and inclusion

|

Financing and Governance

|

Economic Determinants

|

Quality

|

Equipment

|

Community Based Rehabilitation Support

|

Accessibility

|

Eye Health Seeking Behaviour

|

Infrastructure, Resources and Sector Links

|

Environmental and Geographic Determinants

|

Awareness raising

|

Human Resources

|

Non Government Organisations

|

Affordability

|

Vision and Quality of Life

|

Rights, Equity and Inclusion

|

Health Information Systems

|

Advocacy | Satisfaction with services

|

Social capital

|

||

Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices

|

Cost Recovery and Finance Management

|

Sustainability of services

|

Codes: *CDMD = Cambodian Development Mission for Disability **CTEH = CARITAS Takeo Eye Hospital.

Table 5: Summary of key milestones achieved over the life of the Avoidable Blindness Initiative Project of the Kiri Vong District Referral Hospital Vision Centre (KVDRHVC) in Takeo Province.

Table 5: Summary of key milestones achieved over the life of the Avoidable Blindness Initiative Project of the Kiri Vong District Referral Hospital Vision Centre (KVDRHVC) in Takeo Province.

Discussion

This study presents foundational research about the delivery of integrated eye health services (including refraction correction) within the district health system of Takeo Province, Cambodia. Although the period of analysis was limited, the results of this study demonstrate positive outcomes from the newly established eye care service within the district public health system. The increased eye health promotion throughout the province and in particular in Kiri Vong District resulted in improved community awareness and increased number of people seeking eye care services at community health centres and the district hospital.

Our purpose was to test how refraction services and primary eye health care services could be increased and integrated at the district/community level. We embarked on a participatory collaborative working approach to engage all stakeholders in the delivery of eye health care services. Our experience demonstrated the complexity of integrating eye health care (community ophthalmology) within the current public health system, but showed how the public health and community organization stakeholders were mobilized to address avoidable blindness. Local ownership and collaborative planning were key to strengthening the working relationships among health system stakeholders to set a foundation for the long-term viability of the eye health services.

This Cambodian VC is managed within the government health system at the provincial/district level. The initial assistance was provided by Australian Government funding along with the technical guidance by Takeo Eye Hospital and CBM Australia support. In contrast, the LV Prasad Eye Institute VC operation is internally established and managed by the not-for-profit organisation which has control over the hiring of staff as well as the ongoing management of day-to-day processes and procedures.

The proliferation of the term VC in places other than India, has raised questions about the appropriateness of the term, and needs better definition. The governments of Cambodia and Vietnam have been reluctant to use the term ‘Vision Centre’. The Cambodian government has now referred to the VC in its health planning strategy, and it aims to increase eye health care at the district level through the integration of additional VCs by 2020. However, the role and function of the VC must be defined within the country context.

There is renewed interest in how to increase the capacity and coordination of activities within public health institutions/systems to address avoidable blindness in low-resource settings to deliver effective eye care services. [1,16]

Conducting the first Cambodian provincial population-based RAAB survey provided data to make an assessment about the prevalence of blindness and vision impairment. [31] Good cataract surgical outcome (BCVA ≥ 6/18) was 82.5% compared to 75.5% (2007 RAAB). [22,31] In 2012, only 2.8% of respondents indicated a lack of awareness as a barrier to cataract surgery, compared to 12.1% (2007 RAAB).

The lack of specific spectacle making facilities at the district hospital means that a number of patients do not receive the required glasses as patients do not spend money to travel for further assessment. However, this “incremental approach” was a successful strategy to introduce eye health services within the district level health system, but requires further research. [33,35]

This project attempted to address issues associated with disability. [32] The preliminary data recording of self-reported disability provided insight into whether people with other disabilities are accessing eye health care services and warrants further research.

Little has been published about the results of eye health promotion. Our results showed a significant increase in the number of individuals seeking eye health services around World Sight Day in October when radio spots and community message were heavily promoted, suggesting that health promotion efforts were effective.

A limitation of this case study was that the district level VC had only been operational for nearly two years. A follow-up assessment is recommended to determine the long-term sustainability of the program.

Conclusion

The collaborative planning process, involving relevant provincial and district stakeholders from both government and non-profit groups, through the provision of infrastructure, equipment, human resource training, mentorship and community participation, resulted in the successful implementation of a VC as integrated district eye health care services, culminating in improved community awareness and increased number of new people seeking eye care services.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful for the support provided by the Cambodian Ministry of Health, the National Eye Health Program, the provincial and district departments of health as well as staff of the KVDRHVC. Funding was made available from the Australian Government’s Avoidable Blindness Initiative through CBM Australia. Assistance to the KVDRHVC was also provided by CBM Australia and CTEH. The authors have no competing interests.

The authors are grateful for the support provided by the Cambodian Ministry of Health, the National Eye Health Program, the provincial and district departments of health as well as staff of the KVDRHVC. Funding was made available from the Australian Government’s Avoidable Blindness Initiative through CBM Australia. Assistance to the KVDRHVC was also provided by CBM Australia and CTEH. The authors have no competing interests.

References

- Ormsby GM. “Formative research for developing an eye health strategic planning and evaluation framework and checklist for health systems”. University of Melbourne (2016):

- Jose R., et al. “Community Ophthalmology: Revisited”. Indian Journal of Community Medicine35.2 (2010): 356-358.

- Blanchet K and Lindfield R. “Health Systems and eye care: A way forward”. International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (2010):

- Bourne RR., et al. “Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis”. The Lancet Global Health1.6 (2013): e339-e349.

- Pascolini D and Mariotti SP. “Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010”. British Journal of Ophthalmology 96.5 (2012): 614-618.

- World Health Organization. “Universal eye health. A global action plan 2014-2019”. Geneva: World Health Organization (2013):

- World Health Organization. “Everybody's Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes. WHO's Framework for Action”. Geneva: World Health Organization (2007):

- Sachs JD. “Achieving universal health coverage in low-income settings”. Lancet 380.9845 (2012): 944-947.

- Frenk J. “Reinventing primary health care: the need for systems integration”. Lancet 374.9684 (2009): 170-173.

- Naidoo K., et al. “The uncorrected refractive error challenge”. Community Eye Health 27.88 (2014): 74-75.

- Bassett MT., et al. “From the ground up: strengthening health systems at district level”. BMC Health Services Research 13 (2013): S2.

- Du Toit R., et al. “Evidence for integrating eye health into primary health care in Africa: a health systems strengthening approach”. BMC Health Service Research13 (2013): 102-117.

- Atun R., et al. “Integration of targeted health interventions into health systems: a conceptual framework for analysis”. Health Policy and Planning 25.2 (2010): 104-111.

- Dudley L and Garner P. “Strategies for integrating primary health services in low- and middle-income countries at the point of delivery”. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews7 (2011): CD003318.

- Michael Marmot., et al. “Closing the gap in a generation. Health equity through action on the social determinants of health”. Lancet372.9650 (2008): 1661-1669.

- Herring M. “A Strategic Management Framework for Eye Care Service Delivery Organisations in Developing Countries”. University of Adelaide, Australia(2004):

- Rao GN. “An infrastructure model for the implementation of VISION 2020: The Right to Sight”. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology 39.6 (2004): 589-590.

- Rao GN., et al. “Integrated model of primary and secondary eye care for underserved rural areas: The LV Prasad Institute experience”. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology 60.5 (2012): 396-400.

- AusAID. Development for All Strategy. Towards a Disability-inclusive Australian Aid Program 2009-2014. Canberra: Australian Agency for International Development (2009):

- Annear PL., et al. “The Kingdom of Cambodia Health Review”. Health systems in Transition5.2 (2015):

- Cambodian National Institute of Statistics. “General Population Census of Cambodia 2008”. National Institute of Statistics (2010):

- Do S and Limburg H. “Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness in Cambodia: 2007”. National Program for Eye Health, Cambodia(2009):

- Cambodian Government. “National Strategic Plan for Blindness Prevention & Control: 2008-2015”. National Eye Health Program(2011):

- Jacobs B., et al. “From public to private and back again: sustaining a high service-delivery level during transition of management authority: a Cambodia case study”. Health Policy and Planning 25.3 (2010): 197-208.

- Jacobs P and Price N. “Community participation in externally funded health projects: lessons from Cambodia”. Health Policy and Planning 18.4 (2003): 399-410.

- Ormsby G., et al. “The Impact of Knowledge and Attitudes on Access to Eye-Care Services in Cambodia”. The Asia-Pacific Journal of Ophthalmology 1.6 (2012): 331-335.

- Ormsby GM., et al. “Barriers to the uptake of cataract surgery and sys care after community outreach screening in Takeo Province, Cambodia”. Asia-Pacific Journal of Ophthalmology6.3 (2017): 266-272.

- Yin R. “Case Study Research: Design and Methods 4th ed”. German Journal of Research in Human Resource Management(2009): 240.

- Creswell JW and Plano Clark VL. “Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 2nd ed”. Los Angles: Sage (2011):

- World Health Organization. “Everybody’s business. Six Building Blocks”.

- Mörchen M., et al. “Prevalence of blindness and cataract surgical outcomes in Takeo Province, Cambodia”. The Asia-Pacific Journal of Ophthalmology 4.1 (2015): 25-31.

- Mörchen M., et al. “Addressing disability in the health system at CARITAS Takeo Eye Hospital”. Community Eye Health26.81 (2013): 8-9.

- Fricke T., et al. “Global cost of correcting vision impairment from uncorrected refractive error”. Bulletin of the World Health Organization90.10 (2012): 728-738.

- Umar N., et al. “Toward more sustainable health care quality improvement in developing countries: the “little steps” approach”. Quality Management in Healthcare 18.4 (2009): 295-304.

- Lewis D and Webber J. “Disabled people's organisations: a valuable link for eye care workers”. Community Eye Health 26.13 (2013):

Citation:

Gail M Ormsby., et al. “Integrating Eye Health Care within the Public Health System: A Case Study of the Kiri Vong Referral

Hospital Vision Centre, Takeo Province, Cambodia”. Ophthalmology and Vision Science 1.2 (2017): 64-84.

Copyright: © 2017 Gail M Ormsby., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Scientia Ricerca is licensed and content of this site is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Scientia Ricerca is licensed and content of this site is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.