Case Report

Volume 2 Issue 1 - 2018

Problem in Diagnosis and Treatment of Vogt Koyanagi- Harada's Disease in African Black People: One Clinical Observation in Abidjan

Felix-Houphouet Boigny University, 25 bp 1455 Abidjan 25, Côte d’Ivoire

*Corresponding Author: Boni Severin, Felix-Houphouet Boigny University, 25 bp 1455 Abidjan 25, Côte d’Ivoire.

Received: November 17, 2017; Published: February 24, 2018

Abstract

Introduction: Vogt-Koyanagi- Harada syndrome is a severe uveitis associated with extraocular manifestations, rare in African melanoderm. We report a clinical case focusing on the diagnostic difficulties and the evolution of this disease.

Method: We report a case of a 36-year-old patient who consulted for a sudden onset of bilateral visual acuity impairment with severe headache and hypoacusia. Visual acuity at presentation was lower than 1/20 (-log Mar 1.3). Eye fundus examination revealed extensive ranges of bilateral retinal serous detachment. The diagnosis of Vogt-Koyanagi- Harada disease has been made in the presence of suggestive clinical signs. The patient received corticosteroid therapy and evolution was favorable with recovery ad integrum of the visual acuity.

Discussion and Conclusion: Vogt-Koyanagi- Harada disease is a rare pathology in melanoderm people. The ophthalmological and extra-ocular manifestations are similar to those described in the Asian and Mediterranean populations. The visual prognosis is good and requires an adequate management.

Keywords: Glaucoma; Epidemiology; Ophthalmology; Treatment

Abbreviations: Uveitis; Retinal serous detachment; Vogt-Koyanagi- Harada disease

Introduction

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease (VKH) is a severe granulomatous panuveitis associated with extraocular manifestations: neuromeningeal, otological and dermatological [1]. It is thought to be due to autoimmunization with the melanocyte as target cell. This disease is described in the literature as rare in African melanoderm and its diagnosis is based on the presence of ocular and extra-ocular criteria defined by the American Uveitis Study. The illustration of this clinical case shows the difficulties of diagnosis and management of this rare disease in Black people of Africa.

Clinical Case

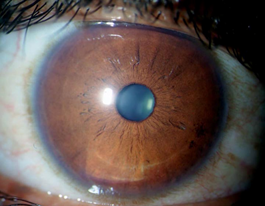

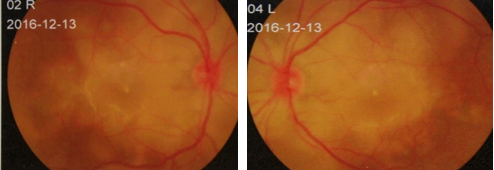

The authors present the observation of a 36-year-old young lady with no particular history such as ocular trauma or ocular surgery. She consulted for a decrease in bilateral visual acuity with brutal installation preceded by violent headache not responding to the usual analgesics and hypoacusia evolving since 2 weeks. At the initial ophthalmological examination, visual acuity was lower than 1/20 (-log Mar 1,3). Anterior segment at slip lamp examination was normal (figure 1) and the eye fundus revealed a discreet hyalitis and a pale gray-looking retina with polylobular bullous zones compatible with extensive bilateral retinal serous detachment ranges (figure 2 and 3).

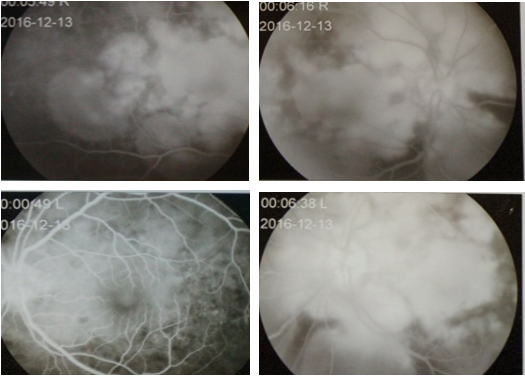

Fluorescein fundus angiographic (FFA) shows at choroidal phase a blockage of choroidal fluorescence and then multiple hyperfluorescent spots increasing gradually during the angiographic sequence. In the later phases the localized hyperfluorescent spots increase in size, coalesce, and expand into the subretinal space in areas of serous detachment (Figure 4,5,6,7)

Figure 4,5,6,7: FFA shows multiple hyperfluorescent spots

increasing gradually during the angiographic sequence.

The neurological examination was normal, as well as the biological results and the analysis of cerebrospinal fluid after lumbar puncture. The general examination of this patient did not find either aphthous or genital ulcer. All etiologies of uveitis frequently observed in our context, including tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, syphilis, and sarcoidosis, have been documented and eliminated. The diagnosis of this incomplete VKH syndrome was based on clinical criteria such as headache, hypoacusia and retinal serous detachment at the fundoscopic examination.

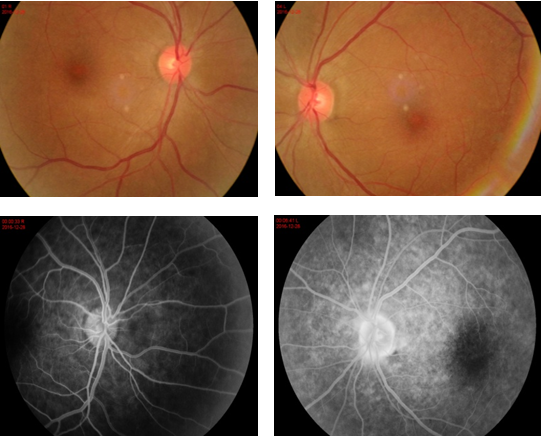

Parenteral administration of Methylprednisolone 1g during 3 days was instituted with oral prednisone relay at 1 mg / kg per day. The clinical course was progressively favorable with a visual acuity at 4/10 (-log Mar 0.4) in both eyes after 2 weeks of treatment, then 6/10 (-log Mar 0.2) at 1 month and a visual recovery at 10/10 (-log Mar 0.0) as well as a normal eye fundus after 2 months of follow-up [Figure 8,9,10,11].

Discussion

Harada's disease is particularly prevalent in women aged from 20 to 50 years, and occurs on a particular genetic background. The diagnostic of VKH syndrome can be difficult, in spite of the established criteria. The literature finds only rare cases in the African melanoderm people [2] and this disease evolves in three phases: a prodromic phase characterized by the presence of neuromeningeal signs, an acute uveitic phase, and a convalescent phase characterized by chorioretinal depigmentation (sunset glow fundus) and changes in the coloring of the skin.

This patient presented only headaches and hypoacusia. The clinical course was not followed by cutaneous lesions. At the prodrome stage, the neurological and otological signs dominate the clinical picture. In presence of neuromeningeal signs, there is a problem of differential diagnosis with acute meningitis, this situation needs a complete neurological examination. The acute phase is characterized by a panuveitis with serous exudative detachment with a severe visual acuity impairment. Episodes of recurrence and complications are encountered at the chronic stage [1,3]. According to the diagnostic procedure, first-line data from the clinical examination and lumbar puncture make possible the establishment of VKH diagnosis. In case of doubt as illustrated in this clinical case, the examination of the eye fundus coupled with the FFA and optical coherence tomography help to make the diagnosis.

VKH syndrome in its incomplete form remains rare and represents only 10% of clinical forms according to some authors [4-5]. This condition is threatening for the visual prognosis and requires early management based on corticosteroids to improve visual function. We noticed a complete visual recovery after the treatment of parenteral methylprednisolone boluses followed by prednisone in degressive dose for 2 months. Emiko in his study showed the immediate effectiveness of corticosteroid bolus by reducing the volume of retinal serous detachments [6]. In addition to its anti-inflammatory effect, methylprednisolone has an early microvascular action that could leads to a rapid recovery of the signs. Methylprednisolone bolus at high dose would provide by its rapid vascular effects, immediate functional benefit in the treatment of VKH disease, as well as a reduction of adverse effects of steroids in short, medium and long terms [7-8].

Conclusion

The diagnosis of VKH disease in black African people is difficult. Ophthalmological and extra-ocular manifestations are similar to those described in the Asian and Mediterranean population. In our professional practice context, clinical signs and fundus examination can lead to a diagnosis evocation. The contribution of retinal angiography and optical coherence tomography is fundamental and useful to confirm the diagnosis. Visual prognosis may be severe but can be improved in case of early and adequate management.

References

- Guenoun J-M., et al. “Le syndrome de Vogt- Koyanagi- Harada: Aspects cliniques, traitement et suivi à long terme dans une population caucasienne et africaine”. Journal Français D'Ophtalmologie 27.9 (2004): 1013-1016.

- Benfdil N., et al. “Le syndrome de Vogt- Koyanagi- Harada chez l’enfant : Diagnostic et prise en charge”. Bulletin De La Societe Belge D'Ophtalmologie 314 (2010): 15-28.

- Blanc F., et al. “Le syndrome de Vogt- Koyanagi – Harada”. Revue Neurologique 161.11 (2005): 1079-1090.

- Shamil L., et al. “Le syndrome de Vogt- Koyanagi- Harada dans sa forme purement oculaire à propos d’un cas”. Pan African Medical Journal 19 (2014): 30.

- Mounach J., et al. “Le syndrome de Vogt- Koyanagi- Harada”. Images en Ophtalmologie 2.3 (2008): 96-108.

- Emiko Y., et al. “Evaluation of pulse corticosteroid therapy for Vogt- Koyanagi – Harada disease assessed by optical coherence tomography”. American Journal of Ophthalmology 134.3 (2002): 454-456.

- Falkenstein E., et al. “Multiple actions of steroid hormones: a focus on rapid, non genomic effects”. Pharmacological Reviews 52 (2000): 513-556.

- Denoyer A., et al. “La maladie de Vogt- Koyanagi- Harada: Intérèts des bolus répétés de corticoides intraveineux à haute dose”. Journal Français D'Ophtalmologie 27 (2004): 404-408.

Citation:

Boni Severin., et al. “Problem in Diagnosis and Treatment of Vogt Koyanagi- Harada’s Disease in African Black People: One

Clinical Observation in Abidjan”. Ophthalmology and Vision Science 2.1 (2018): 195-199.

Copyright: © 2018 Boni Severin., et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Scientia Ricerca is licensed and content of this site is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Scientia Ricerca is licensed and content of this site is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.